Contents

- Introduction

- What is XML?

- What is XSL?

- Necessary and Helpful Software Packages

- Choosing and Preparing XML Data

- Creating and Testing Your XSL File

- Populating Your Outputs

- Printing Values

- Sorting Results

- Filtering Results

- Conclusion

Introduction

The day before your colleague is due to give a seminar on Slave Rebellions in the New World, he phones you to say he is ill and needs you to cover his sessions. You decide to compile a selection of primary sources to work through in class. You find some websites and readers with good sources, but scanning or cutting-and-pasting them into a new document is time consuming; the formatting and citations are inconsistent and you begin to wonder if the ones you have chosen work well together. One site allows you to download an XML version of all its sources, but there are so many records, and so much metadata, that you cannot find the material you want quickly.

Or perhaps…

You find an old copy of Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania (1952) and wish that you could run a statistical analysis on the appearance of certain phrases in certain locations. Fortunately, King’s College London has produced an extensive e-version of the text with images, translations and location information. You can search through the material manually using the full-text search on the site, but curating the information you want, in the format you need to run an analysis, will take time.

Then again…

You are starting a new project analysing book auction catalogues from the early seventeenth century. You start recording the publication details and auction listings into a series of Word documents and Excel spreadsheets. A month into the project, you are invited to present your research to the Pro-Vice Chancellor. Your head of department suggests that you create a ‘snazzy’ set of slides and handouts to help her understand your project. You have some preliminary conclusions about the material, but the data is scattered in several places and formatting it properly will take more time than you have.

In all three of these situations, a basic understanding of XML, and its sister-language XSL, could have saved you time and aggravation. This tutorial will provide you with the ability to convert or transform historical data from an XML database (whether a single file or several linked documents) into a variety of different presentations—condensed tables, exhaustive lists or paragraphed narratives—and file formats. Whether filtering a large database or adding formatting such as headings and pagination, XSL offers historians the ability to reshape databases to support their changing research or publication needs.

What is XML?

eXtensible Markup Language (XML) is a highly flexible method for encoding or structuring your data. Unlike Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), which has a set vocabulary, XML is extensible; it can be expanded to include whatever sections, sub-section, and sub-sub-sections you need in order to store your data in the way you wish.

A database can be made up of one or more XML files and each file has the same basic structure. Each section, or layer, of the file is surrounded by a set of elements. An element is, essentially, a category or name for the type of data you are providing. Like Russian Nesting Dolls, each level of elements exists entirely within another one. The top-level element encloses the entire database. Each element within the top-level element is a child of that element. Likewise, the element surrounding a child element is called the parent element.

<top>

<parent>

<child></child>

</parent>

</top>

Every element can, depending on the rules of your database, have a value (textual or numerical) as well as any number of child elements.

<top>

<parent>

<child_1>value</child_1>

<child_2>value</child_2>

<child_3>value</child_3>

</parent>

</top>

They can also have attributes, which can be thought of as metadata for the element. Attributes can, for example, help you distinguish between different types of values without having to create a new type of element.

<top>

<name>

<last>Crockett</last>

<first type="formal">David</first>

<first type="informal">Davy</first>

</parent>

</top>

Once you are given an XML database, or have stored your own data within one, you can use XSL to sort, filter and display this information in (almost) any way you wish. You can even break open OpenXML files, such as Word (.docx) or Excel (.xslx) files, and see or remove any additional information that Microsoft has inserted into your documents, such as tags identifying geographical locations.

A more detail discussion of XML, its structure, and its use in the humanities, is available from the Text Encoding Initative.

What is XSL?

eXtensible Stylesheet Language (XSL) is the natural complement to XML. At its most basic level, it provides layout and formatting instructions in much the same way as Cascading Stylesheets (CSS) do for HTML files. This allows you to transform your plain-text data into richly formatted text, as well as dictate its layout on a screen or in print, without altering your original data files. At a more advanced level, it also allows you to sort or filter your records based on particular critera, or create and display compound or derived values based on your original dataset.

By keeping your data (XML) and formatting instructions (XSL) separate, you are able to refine and alter your layout without the risk of compromising the structure of your data. You are also able to create a number of different styles, each serving a different purpose, and apply them as necessary to a single data set. In practice, this means only having to update your data in one place, even if you export it to many different documents.

The following tutorial will therefore explain

- Editors: The tools needed to create XSL transformation files

- Transformers: The tools needed to apply your XSL transformation instructions to your XML database

- Choosing and Preparing XML Data: How to connect your database to your XSL transformation instructions

as well as walk you through the creation of some of the most common transformations intructions, including

- Printing Values: How to print or display your data

- For-Each Loops: How to display particular data for each record

- Sorting Results: How to display your data in a particular order

- Filtering Results: How to select which records you display

Necessary and Helpful Software Packages

Editors

One of the advantages of storing data in a plain-text format is the ease of obtaining appropriate software for viewing and manipulating it. For the purposes of this tutorial, you can use any plain-text editor, such as Notepad (Windows) or TextEdit (Mac OS), but should not use a WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) word processor such as Microsoft Word, as these often insert non-ascii characters, such as curly quotation marks, that will prevent your XSL from processing correctly. This tutorial will assume you are using Notepad or TextEdit.

Although these will provide everything you need, you may prefer to download a more advanced editor, such as Notepad++ or Atom. These free editors maintain the plain-text format of your data while providing you with different colour schemes (such as green-on-black or brown-on-beige) as well the ability to collapse (hide) sections or easily comment-out (temporarily disable) sections of your code.

When you become more comfortable with XML and XSL, and are ready to tackle more complicated transformations, you may want to consider using a dedicated XML editor, such as OxygenXML.

Transformers

Once you have obtained your preferred text editor, you will need to obtain an XSL transformer. There are two ways to use XSL stylesheets to transform your XML data: on the command line or through an embedded transformer within another programme. Although there are many stand-alone programmes for XSL transformation, you can also undertake simple transformations using an internet browser.

Although Chrome and Safari’s security features make in-browser transformations difficult, some other internet browsers, such as (Internet Explorer and Firefox), include an XSL 1.0 transformer, which will provide all of the functionality that you will need for this tutorial. If you don’t already have one of these browsers on your computer, download and install whichever you feel most comfortable using and then proceed to the next section.

Choosing and Preparing XML Data

In order to begin transforming XML, you will need to obtain a well-formed dataset. Many online historical databases are built upon XML and provide their data freely. This tutorial will make use of the Scissors and Paste Database.

The Scissors and Paste Database is a collaborative and growing collection of articles from British and imperial newspapers in the 18th and 19th centuries. Its original purpose was to allow for careful comparisons of reprints (copies) that appeared in multiple newspapers as well as to detect similarly themed articles across different English-language publications. Like many XML databases, Scissors and Paste contains both data (the article’s text), formatting information (such as italics and justification), and metadata. This metadata includes documentation about the particular article, such as its pagination and printing date, information about the newspaper in which it was published, and the themes, individuals or locations mentioned in the text.

As of 2015, the database contained over 350 individual articles, each with attached metadata. Although some researchers may need all of this information, most will only be interested in a subsection of the data—a particular year, theme or publication. By using XSL, these researchers can quickly filter out the information they do not need or re-arrange the material in the way that is most helpful for their project. For example, the module tutor in our introduction or a researcher who wants a simple table of the dates, publications and page numbers of humorous articles within the database. Both can be quickly created using XSL.

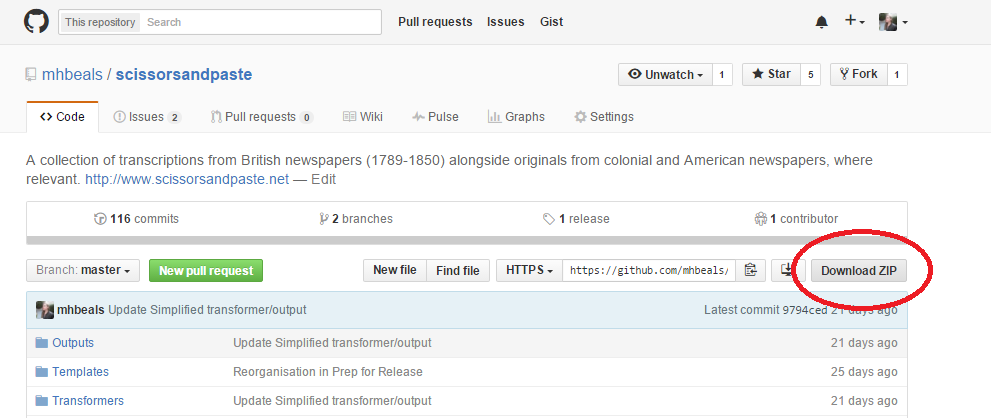

To begin work with the Scissors and Paste Database, visit its Github repository. On the right-hand side of the screen, you will see the option to Download Zip. Save this to your computer desktop or primary documents folder.

Figure 1: Downloading Your Data

Alternatively, you can also download the scissors and paste file here.

Open the ZIP file and you will find a folder entitled scissorsandpaste-master. Extract this folder by either using the extract button of your unzipping programme or by dragging and dropping the folder onto your desktop.

This data package has three main components

- TEISAP.XML: The central XML database

- Transformers: A collection of XSL stylesheets

- Outputs: Outputs derived from the database using the XSL stylesheets

The package also includes

- A Template, for anyone wishing to contribute to the database

- A README file, providing information about the database

- A Cite file, explaining the preferred way to cite the database

- A License file, explaining the terms of use

Once you have completed the tutorial, you can explore the different XSL stylesheets (transformers) included here, and their associated outputs, to discover additional possibilities for your own datasets.

The main TEISAP.XML database has been encoded to Text-Encoding Initiative (TEI) standards and includes a significant amount of metadata. For the purposes of this tutorial, however, we will be using a simplified version of the database that focuses on some of the core historical data.

Open the outputs folder and continue into the XML folder. Here you will find a folder entitled Simplified. Copy the SimplifiedSAP.xml file to your desktop.

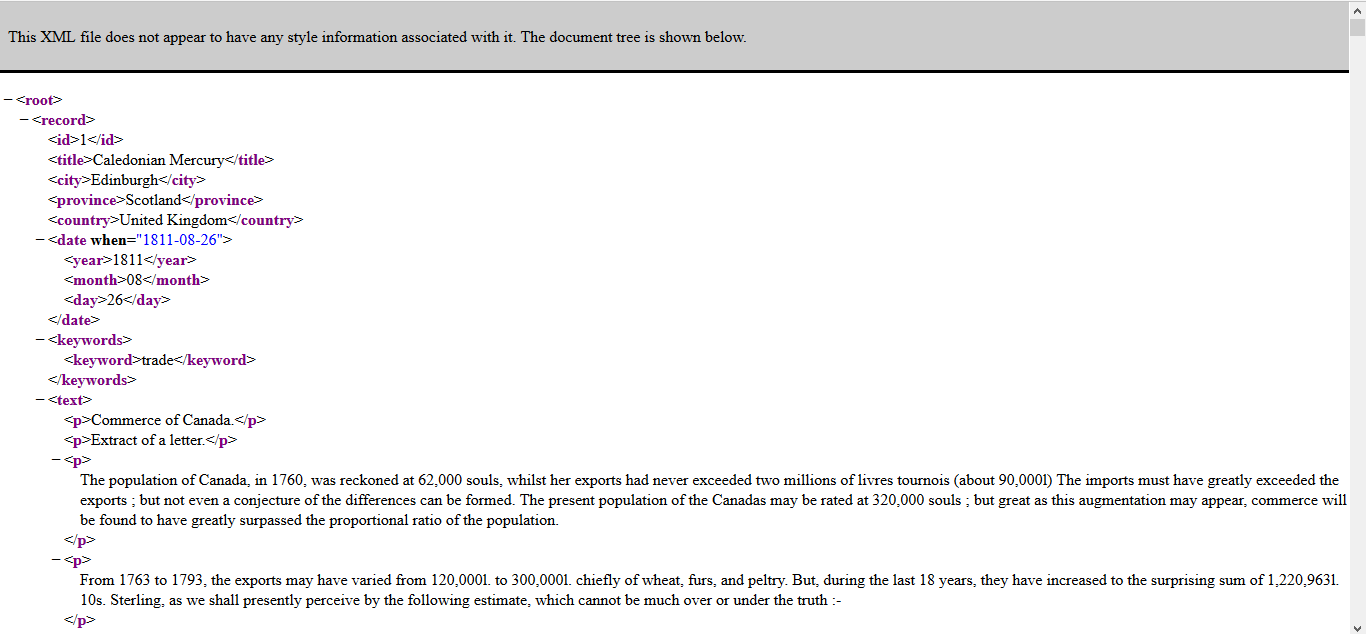

Using your chosen web browser, open SimplifiedSAP.xml and examine the file. You can do this using the standard ‘Open’ function of your browser’s tool bar, or by dragging-and-dropping the file from your desktop into the browser window.

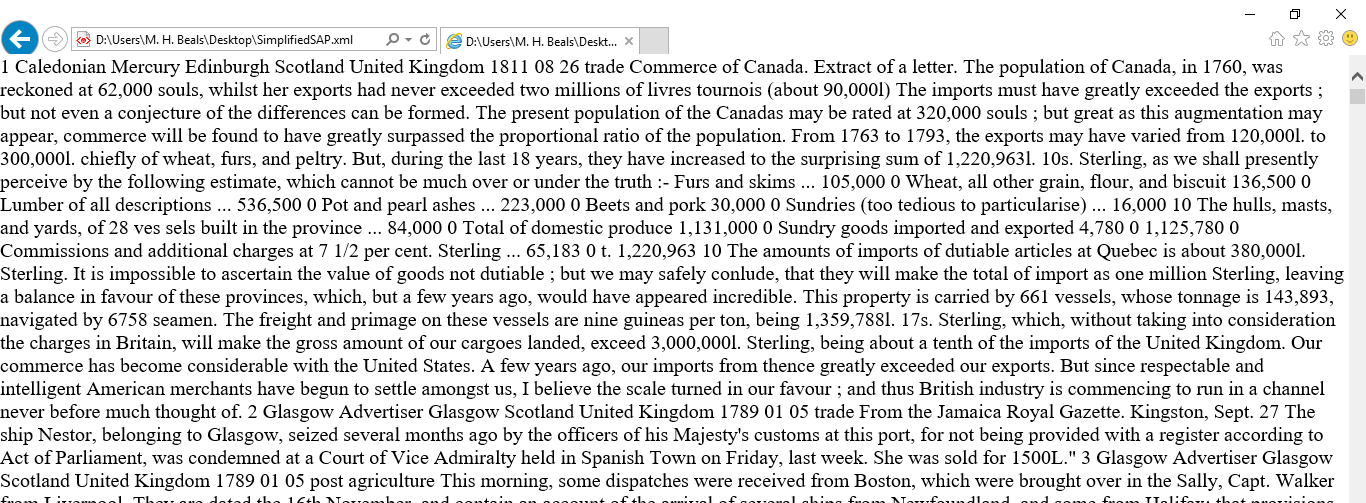

Figure 2: Viewing the XML

The first line of the XML database is <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>, which indicates the version of XML used (1.0) and the encoding method of the text (UTF-8). The second line is <root>, which has a matching line, </root>, at the end of the file.

<root> is the top-level element of this database and surrounds all the records within it. Each individual record, containing the information for one historical newspaper article, is opened by the element <record> and closed with the element </record>.

Within these records are a number of different child elements. The Text-Encoding Initiative allows for hundreds of different sub-elements to fit a very wide range of data. Moreover, the beauty of XML is that you can name your elements anything you like (with a few small exceptions). In the Scissors and Paste Database, each record has the following elements:

- id: The ID number of the record

- title: The title of the newspaper

- city: The city of the newspaper

- province: The province or administrative region of the newspaper

- country: The country of the newspaper

- date: The full ISO date of the article

- year: The year of publication

- month: The month of publication

- day: The day of publication

- keywords: The section containing keywords describing the article

- keyword: An individual keyword describing the article

- headline: The headline of the article. This may be blank.

- text: The section containing the text of the article

- p: An individual paragraph within the text.

These are the different types of data that you will be able to use in creating your outputs.

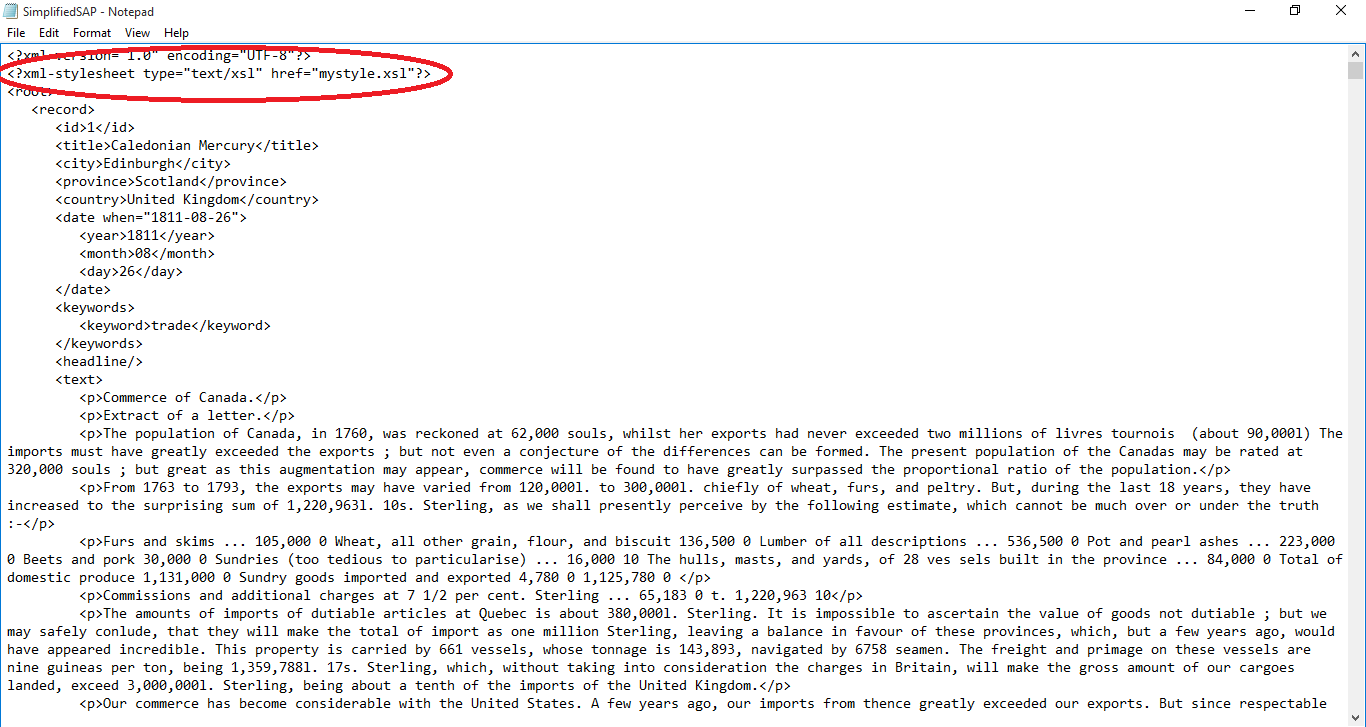

In order to undertake a browser-based transformation, you will need to put in a stylesheet reference within your xml file.

Using your prefered text editor, open SimplifiedSAP.xml and examine the contents.

Create a new line underneath <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>. On this new line, type

<?xml-stylesheet type="text/xsl" href="mystyle.xsl"?>

and save your XML file.

Figure 3: Adding a Stylesheet Reference to your XML

This line points to the XSL file you are about to create and will therefore set it as the default XSL stylesheet for this database. It does not matter what you name the .xsl file, so long as you remember it for the next step.

Creating and Testing Your XSL File

It is now time to create your XSL file. In your text editor, create a new file and save it as mystyle.xsl (or whatever you named your .xsl in the previous step), ensuring that it is in the same folder as your XML file (for example, your Desktop or Simplified.)

The first two lines of you XSL file should be the following:

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

The first line documents that you are using XSL version 1.0 and the standards (or namespace) established by the World Wide Web Consortium, whose web address you have listed. The second line tells your transformer what sort of output you would like to create. In this case, you are indicating that you will be creating a plain-text file. You could also have written “xml” or “html”.

Every time you open an element <element> you will need to close it </element>, otherwise you will receive an error. Close your stylesheet by adding the following as the final line of your file:

</xsl:stylesheet>

The next part of your XSL stylesheet will be the main template, or formatting instructions, for your output. On a new line, directly underneath <xsl:output method="text"/> type

<xsl:template match="/">

</xsl:template>

It is between these two elements that you will put all your layout instructions.

You have written ”/” in your match attribute to indicate that you will be referring to everything within the XML file. You could have also used “root”, which would have indicated that you were only using data within the root element. However, using “root” may cause unexpected errors later on, so it is best practice to use “/” for your main template.

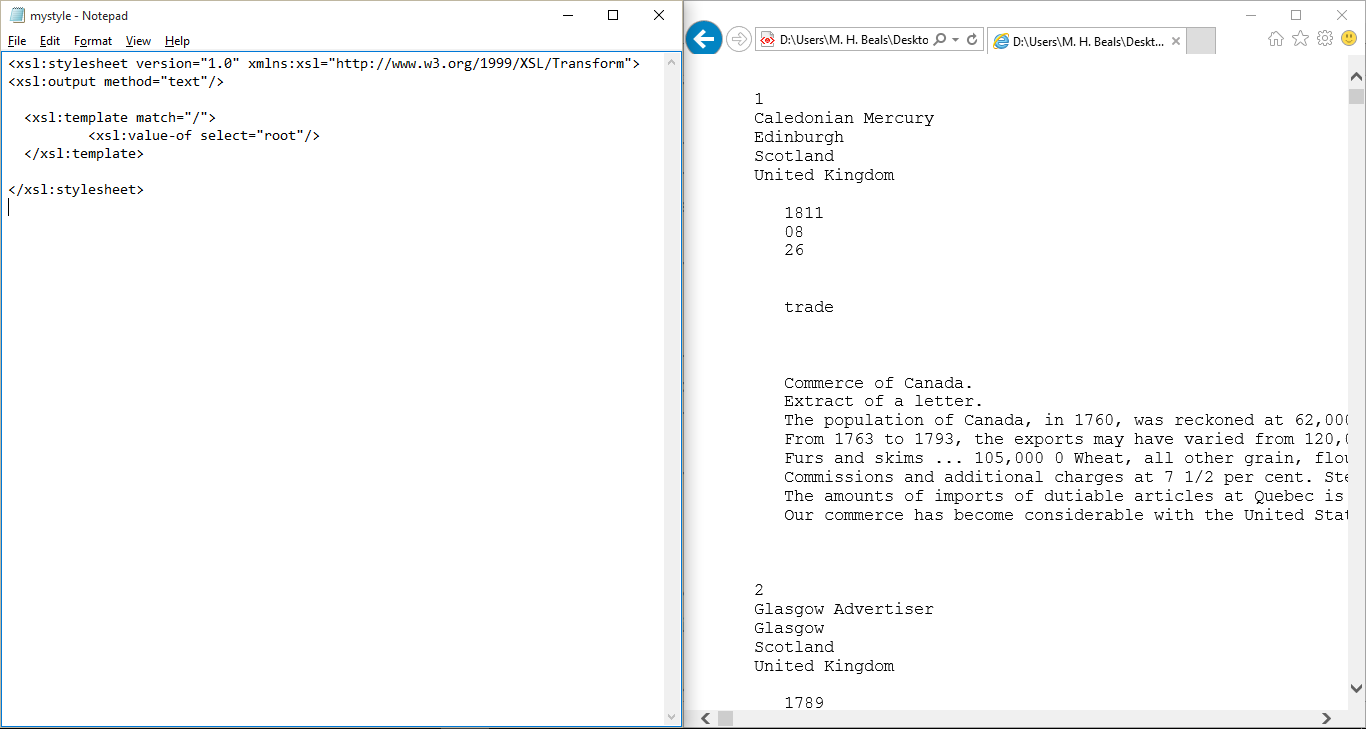

Your file should now look like this:

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

Save your file. For the remainder of the tutorial, remember to save your file after each change you make.

N.B. If you are using TextEdit, you will not be able to save the file as an XSL directly. Instead, save as a PlainText (.txt) file and close the document. Then, locate the file within Finder and rename it, changing the extension from .txt to .xsl. Now, reopen the file within TextEdit to continue.

In between your template elements, type <xsl:value-of select="root"/> You do not need to do so on a new line, but doing so will make your stylesheet more readable. You’ll notice that I didn’t include a </root>. This is because <xsl:value-of select="root"/> is self-closing; the / at the end of the element closes it immediately.

After you save your file, open your preferred web browser (IE or Firefox) and use it to open your XML file. The simplest way to do this is to drag the xml file (the file with the Scissors and Paste data) into your browser window, but you can also open it using your browser’s standard Open File function.

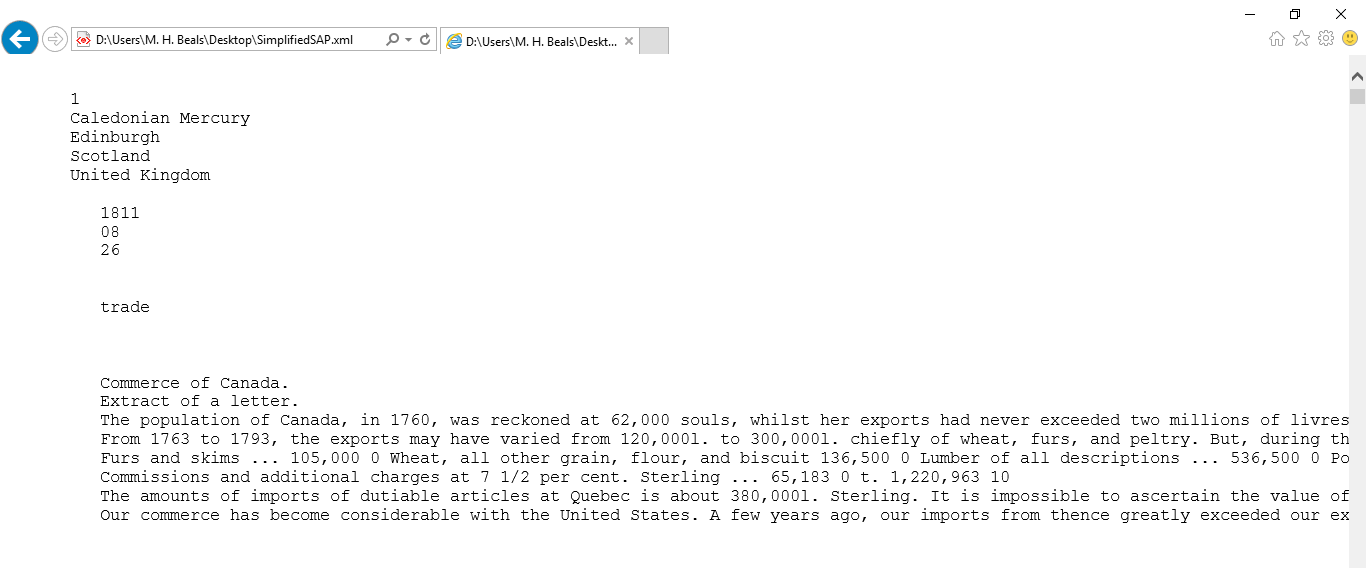

You should now see the text from your data file with line breaks but without its structuring elements, as pictured below.

Figure 4: Initial Text Output

If you see the XML data without any formatting, or an error message, go back and double-check your stylesheet reference within you XML file as well as your XSL stylesheet. Even a small typographical error will prevent the transformer from rendering the output.

Figure 5: Unstructured ‘Error’ Output

Once you have successfully rendered the data as a plain-text output, organise your desktop so that you can move quickly between your text editor and your browser. I suggest docking (snapping) your browser window to one side of the screen and your editor to the other.

Figure 6: Organising Your Workspace

Populating Your Outputs

Your single line of code <xsl:value-of select="root"/> printed the entire database in plain-text format. If you look at the components of this line, you can see why:

-

xsl:value-of: An instruction for printing the value of an element; that is, the text between the opening and closing tag of an element within the XML file.

-

select=”root”: An instruction that explains which element it should print the value of. Unless you instruct it otherwise, pointing to a parent (outside) element will also tell the transformer to print the values of any child (inside) elements as well. Thus, pointing to root also prints id, title and so on.

Printing Values

In order to print the value of a particular data element, you simply need to replace the “root” with another element name. In your XSL stylesheet, replace root with title. Save your file and refresh your browser (usually ctrl+F5 or cmd+r) to see your changes.

It didn’t work? That is because we only gave the transformer part of the instructions it needed.

Parents and Children

Title is not the top-level element, so we must explain to the transformer how to get to the element we mean. This more specific direction is known as the XPATH, and works in a similar way to the file paths on your computer. Replace title with root/record/title.

<xsl:value-of select="root/record/title"/>

Save and refresh your browser.

The browser should now display “Caledonian Mercury”, the first title in our database. Where are the rest? Although, we have over 300 title values in the database, we did not specify which we wanted the transformer to print, so it assumed we meant the first one, and only the first one.

For-Each Loops

To a human being, it may seem natural that we wanted all the title values, but the transformer does not know this by default. Instead, we must create a For-Loop.

A For-Loop tells the transformer that for a certain condition, it should loop through the entire database and follow the instructions each time the data meets that criteria.

Create a new line after <xsl:template match="/"> and insert <xsl:for-each select="root/record">. This tells the transformer that for each record within the root element, it should take some action.

Remove root/record from your <xsl:value-of> element. It should now simply say title, because we are now already within a root/record element. After your <xsl:value-of>, add a new line that closes the <xsl:for-each> element, </xsl:for-each>

Your file should now look like this:

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:for-each select="root/record">

<xsl:value-of select="title"/>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

Here you can see that your template has three lines of code.

- An opening element for your for-loop

- An instruction to print the value of title

- A closing element for your for-loop

Save your file and refresh your browser. You should now have a very messy line of text, listing the value of every title element in the database. You can organise this data by instructing the transformer to add a new line after each entry.

At the end of your value-of line, type <xsl:text>

</xsl:text> to add a line break.

is the ISO 10646 hex code for a new line and the <xsl:text> element tells the transformer to print the value as plain text.

Depending on the type of outputs you are using, some special characters, particularly multiple spaces or line breaks, may not render correctly if entered on their own. Using <text> elements ensures that your text renders exactly the way you intend it to.

Save and refresh your browser to see your changes. Using this information, you should now be able to print the value of any element for each record in the database.

Exercise A:

Note: Possible solutions for the following exercises are located at the end of the tutorial.

Print an inventory of the records in database, displaying the id, title and date of each record. A solution to this and the following exercises is available at the end of the tutorial.

Exercise B:

Print the text of all the articles in the database, displaying the ID number in brackets at the start of each article.

Attributes

Not all data is stored as the value of an element. Some data is stored as the value of an attribute of that element. For example the <date> element has an attribute called when with the value of the date of the article.

<date when="1815-01-12"/>

To print the value of when you will need to reference the attribute using @when

<xsl:value-of select="date/@when"/>

Exercise C

Create an inventory of records in the database, listing the title of the newspaper followed by the date of publication.

Sorting Results

This database was compiled as data was collected, rather than by date or title. To re-sort it, you can add a <xsl:sort> instruction to the top of any for-loop, immediately following the <xsl:for-each> element. This instruction has several optional attributes that will dictate how your data is sorted

- select: the name of the element to sort the data by

- order: informs the transformer if the data should be sorted in an ascending or descending order

- data-type: informs the transformer if the data is text or a number

It must be attributed in this order. For example, to sort the id in reverse order, use

<xsl:sort select="id" order="descending" data-type="number"/>

You can sort by an element even if you do not print that element in your output.

Exercise D

Print the text of all the articles in the database, sorting from earliest to latest. For the purposes of the sort function, treat dates as text.

Filtering Results

So far, you have printed all the records contained in the database. If you only want a selection of records, you will need to filter the results using an if statement. An <xsl:if> element has one attribute, which is a test condition. If the condition is true, the transformer will follow the instructions within the <xsl:if> element. If not, it will ignore these statements and move onto the next part of the template.

For example, to print the id numbers of all the records from 1815, you would type

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:for-each select="root/record">

<xsl:if test="date/year='1815'">

<xsl:value-of select="id"/>

<xsl:text>

</xsl:text>

</xsl:if>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

If you want to exclude 1815, use date/year != '1815' instead. != means not equal to.

Exercise E

Using all you have learned so far, create a list of records from 1789, starting with the most recent, listing the id, title, and date of each record. Separate the data elements with commas and place each record on it own line.

When you are satisfied with your results, save the file, using your browser’s Save As function, as sap_itd.csv. You now have a comma-separated data file that can be opened and manipulated in any spreadsheet programme, such as Excel or CALC.

Conclusion

You now know the basics of XSL stylesheet creation. With this information you can create a range of outputs including plain-text, comma-separated, tab-separated and markdown files. You can also create webpages by changing your <xsl:output> method to html and wrapping your <xsl:value-of> commands in the appropriate HTML tags.

There are many more transformation commands that you can use to further customise your outputs. Some of these require the use of a 2.0 transformer, but the above should cover most of your day-to-day transformation needs.

Once you are comfortable using the commands listed here, explore the transformers folder of the Scissors and Paste Database to see further examples of how to transform XML structured data.

Exercise Solutions

Introduction (Primary Source Reader)

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="html"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<html>

<body>

<xsl:for-each select="root/record">

<xsl:if test="keywords/keyword = 'slave insurrections'">

<h2>

<i><xsl:value-of select="title"/></i>, <xsl:value-of

select="substring(date/@when, 9, 2)"/>

<xsl:text> </xsl:text>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '01'">January</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '02'">February</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '03'">March</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '04'">April</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '05'">May</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '06'">June</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '07'">July</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '08'">August</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '09'">September</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '10'">October</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '11'">November</xsl:if>

<xsl:if test="substring(date/@when, 6, 2) = '12'">December</xsl:if>

<xsl:text> </xsl:text>

<xsl:value-of select="substring(date/@when, 1, 4)"/>

<xsl:text>

</xsl:text></h2>

<xsl:for-each select="text/p">

<p>

<xsl:value-of select="."/>

</p>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:if>

</xsl:for-each>

</body>

</html>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

Exercise A

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:for-each select="root/record">

<xsl:value-of select="id" />, <xsl:value-of select="title" />, <xsl:value-of select="date" /><xsl:text>

</xsl:text>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

Exercise B

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:for-each select="root/record">

[<xsl:value-of select="id"/>]

<xsl:value-of select="text"/>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

To remove the indentation of your text, you will need to take more direct control of your whitespace by using line-breaks before each ID number and paragraph, as seen below. In the second for-loop, we use . to refer to the p in select="text/p". Using p would be interpreted as text/p/p, which does not exist.

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:for-each select="root/record"><xsl:text>

</xsl:text>[<xsl:value-of select="id"/>]<xsl:text>

</xsl:text><xsl:for-each select="text/p"><xsl:value-of select="."/><xsl:text>

</xsl:text></xsl:for-each></xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

Exercise C

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:for-each select="root/record">

<xsl:text>

</xsl:text>

<xsl:value-of select="title"/>

<xsl:text> </xsl:text>

<xsl:value-of select="date/@when"/>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

You’ll notice I used   in between my two values. This is the HEX code for a space. You could have also used a literal space, but this is may not render correctly in all cases. You could have also used a comma or any other divider.

Exercise D

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text" />

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:for-each select="root/record">

<xsl:sort select="date/@when" order="ascending" data-type="text"/>

<xsl:for-each select="text/p">

<xsl:text>

</xsl:text><xsl:value-of select="."/>

</xsl:for-each>

<xsl:text>

</xsl:text>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>

Exercise E

<xsl:stylesheet version="1.0" xmlns:xsl="http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform">

<xsl:output method="text"/>

<xsl:template match="/">

<xsl:for-each select="root/record">

<xsl:sort select="date/@when" order="descending" data-type="text"/>

<xsl:if test="date/year = '1789'">

<xsl:value-of select="id"/>, <xsl:value-of select="title"/>, <xsl:value-of select="date/@when"/><xsl:text>

</xsl:text>

</xsl:if>

</xsl:for-each>

</xsl:template>

</xsl:stylesheet>