Contents

- Introduction and Lesson Scope

- Linked open data: what is it?

- The role of the Uniform Resource Identifier (URI)

- How LOD organises knowledge: ontologies

- RDF and data formats

- Querying RDF with SPARQL

- Further reading and resources

- Acknowlegements

Introduction and Lesson Scope

This lesson offers a brief and concise introduction to Linked Open Data (LOD). No prior knowledge is assumed. Readers should gain a clear understanding of the concepts behind linked open data, how it is used, and how it is created. The tutorial is split into five parts, plus further reading:

- Linked open data: what is it?

- The role of the Uniform Resource Identifier (URI)

- How LOD organises knowledge: ontologies

- The Resource Description Framework (RDF) and data formats

- Querying linked open data with SPARQL

- Further reading and resources

The tutorial should take a couple of hours to complete, and you may find it helpful to re-read sections to solidify your understanding. Technical terms have been linked to their corresponding page on Wikipedia, and you are encouraged to pause and read about terms that you find challenging. After having learned some of the key principles of LOD, the best way to improve and solidify that knowledge is to practise. This tutorial provides opportunities to do so. By the end of the course you should understand the basics of LOD, including key terms and concepts.

If you need to learn how to explore LOD using the query language SPARQL, I recommend Matthew Lincoln’s ‘Using SPARQL to access Linked Open Data’, which follows on practically from the conceptual overview offered in this lesson.

In order to provide readers with a solid grounding in the basic principles of LOD, this tutorial will not be able to offer a comprehensive coverage of all LOD concepts. The following two LOD concepts will not be the focus of this lesson:

- The semantic web and semantic reasoning of datasets. A semantic reasoner would deduce that George VI is the brother or half-brother of Edward VIII, given the fact that a) Edward VIII is the son of George V and b) George VI is the son of George V. This tutorial does not focus on this type of task.

- Creating and uploading linked open datasets to the linked data cloud. Sharing your LOD is an important principle, which is encouraged below. However, the practicalities of contributing your LOD to the linked data cloud are beyond the scope of this lesson. Some resources that can help you get started with this task are available at the end of this tutorial.

Linked open data: what is it?

LOD is structured information in a format meant for machines, and is thus not necessarily easy on the eye. Don’t be put off by this, as once you understand the principles, you can get a machine to do the reading for you.

If all datasets were openly published, and used the same format for structuring information, it would be possible to interrogate all of the datasets at once. Analysing huge volumes of data is potentially much more powerful than everyone using their own individual datasets dotted around the web in what are known as information silos. These interoperable datasets are what LOD practitioners are working towards.

To achieve this goal, while working with LOD, always remember the following three principles:

- Use a recognised LOD standard format. In order for LOD to work, the data must be structured using recognised standards so that computers interrogating the data can process it consistently. There are a number of LOD formats, some of which are discussed below.

- Refer to an entity the same way other people do. If you have data about the same person/place/thing in two or more places, make sure you refer to the person/place/thing the same way in all instances.

- Publish your data openly. By openly I mean for anyone to use without paying a fee and in a format that does not require proprietary software.

Let’s start with an example of data about a person, using a common attribute-value pair approach typical in computing:

person=number

In this case, the ‘attribute’ is a person. And the value - or who that person is - is represented by a number. The number could be randomly assigned, or you could use a number that was already associated with that individual. The latter approach has big advantages: if everybody who creates a dataset that mentions that person uses exactly the same number and in exactly the same format, then we can reliably find that individual in any dataset adhering to those rules. Let’s create an example using Jack Straw: both the name of a fourteenth-century English rebel and a UK cabinet minister prominent in Tony Blair’s administration. It is clearly useful to be able to differentiate the two people who share a common name.

Using the model above in which each person is represented by a unique number, let’s make the UK minister Jack Straw, number 64183282. His attribute-value pair would then look like this:

person=64183282

And let’s make Jack Straw described by the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as ‘the enigmatic rebel leader’, number 33059614, making his attribute-value pair look like this:

person=33059614

Providing everyone making LOD uses these two numbers to refer to the respective Jack Straws, we can now search for person 64183282 in a linked open dataset and can be confident that we are getting the right person - in this case, the minister.

The attribute-value pairs can also store information about other types of entities: places, for example. Jack Straw the modern politician was a member of British Parliament, representing the seat of Blackburn. There’s more than one place in the UK called Blackburn, not to mention other Blackburns around the world. Using the same principles as outlined above, we can disambiguate between the various Blackburns by assigning a unique identifier to the correct place: Blackburn in Lancashire, England.

place=2655524

At this point you might be thinking, “that’s what a library catalogue does”. It’s true that the key idea here is that of the authority file, which is central in library science (an authority file is a definitive list of terms which can be used in a particular context, for example when cataloguing a book). In both of the examples outlined above, we have used authority files to assign the numbers (the unique ids) to the Jacks and to Blackburn. The numbers we used for the two Jack Straws come from the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF), which is maintained by a consortium of libraries worldwide to try to address the problem of the myriad ways in which the same person might be referred to. The unique identifier we used for the Blackburn constituency came from GeoNames, a free geographical database.

But let’s try to be more precise by what we mean by Blackburn in this instance. Jack Straw represented the parliamentary consitituency (an area represented by a single member of parliament) of Blackburn, which has changed its boundaries over time. The ‘Digging Into Linked Parliamentary Data’ (Dilipad) project (on which I worked), produced unique identifiers for party affiliations and constituencies for each member of parliament. In this example, Jack Straw represented the constituency known as ‘Blackburn’ in its post-1955 incarnation:

blackburn1955-current

As VIAF is a well respected and well looked after authority file of notable people, it was an obvious set of identifiers to use for Jack Straw. As the constituency represented by Straw was covered perfectly by the authority files created by the Dilipad project, it too was a logical authority file to use. Unfortunately, it is not always so obvious which of the published lists online is best to use. One might be more widely used than another, but the latter might be more comprehensive for a particular purpose. GeoNames would work better than the Dilipad identifiers in some cases. There will also be cases where you can’t find a dataset with that information. For example, imagine if you wanted to write attribute-values pairs about yourself and your immediate family relationships. In this case you would have to invent your own identifiers.

This lack of consistent authority files is one of the major challenges LOD is facing at the moment. Tim Berners-Lee, who came up with a way of linking documents together over a network, and thus created the World Wide Web, has long been a leading proponent of LOD. To encourage more use of LOD he has suggested a ‘five-star rating system’ to encourage everyone to move as far towards LOD as possible. In essence, he believes that it’s good to publish data openly, especially if it uses open formats and public standards, but best if it links to other people’s data too.

Once all elements are assigned unique identifiers, the next key step in creating LOD is to have a way of describing the relationship between Jack Straw (64183282) and Blackburn (blackburn1955-current). In LOD, relationships are expressed using what’s known as a ‘triple’. Let’s make a triple that represents the relationship between Jack Straw and his constituency:

person:64183282 role:representedInUKParliament constituency:"blackburn1955-current" .

The presentation (or syntax) of triples, including the punctuation used above, will be discussed later, in the section on RDF and data formats. For now, focus on the basic structure. The triple, not surprisingly, has three parts. These are conventionally referred to as subject, predicate and object:

| the subject | the predicate | the object |

|---|---|---|

| person 64183282 | representedInUKParliament | “blackburn1955-current” |

The traditional way to represent a triple in diagrammatic form is:

the classic way to represent a triple

So our Jack Straw triple, in more human-readable form, could be represented like this:

triple diagram showing that Jack Straw represented Blackburn

For now there are three key points to remember:

- LOD must be open and available to anyone on the internet (otherwise it isn’t ‘open’)

- LOD advocates aim to standardise ways of referring to unique entities

- LOD consists of triples which describe relationships between entities

The role of the Uniform Resource Identifier (URI)

An essential part of LOD is the Uniform Resource Identifier, or URI. The URI is a reliably unique way of representing an entity (a person, an object, a relationship, etc), in a fashion that is usable by everyone in the world.

In the previous section we used two different numbers to identify our two different Jack Straws.

person="64183282"

person="33059614"

The problem is that around the world there are many databases that contain people with these numbers, and they’re probably all different people. Outside of our immediate context these numbers don’t identify unique individuals. Let’s try to fix that. Here are these same identifiers but as URIs:

http://viaf.org/viaf/64183282/

http://viaf.org/viaf/33059614/

Just as the unique number disambiguated our two Jack Straws, the full URI above helps us disambiguate between all of the different authority files out there. In this case, it’s clear that we are using VIAF as our authority file. You have already seen this form of disambuguation many times on the web. There are many websites round the world with pages called /home or /faq. But there is no confusion because the domain (the first part of the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) - eg. bbc.co.uk) is unique and thus all pages that are part of that domain are unique from other /faq pages on other websites. In the address http://www.bbc.co.uk/faqs it is the bbc.co.uk part which makes the subsequent pages unique. This is so obvious to people who use the web all the time that they don’t think about it. You probably also know that if you want to start a website called bbc.co.uk you can’t, because that name has already been registered with the appropriate authority, which is the Domain Name System. The registration guarantees uniqueness. URIs also have to be unique.

While the examples above look like URLs, it is also possible to construct a URI that looks nothing like a URL. We have many ways of uniquely identifying people and things and we rarely think or worry about it. Barcodes, passport numbers, and even your postal address are all designed to be unique. Mobile phone numbers are frequently put up as shop signs precisely because they are unique. All of these could be used as URIs.

When we wanted to create URIs for the entities described by the ‘Tobias’ project, we chose a URL-like structure, and chose to use our institutional webspace, setting aside data.history.ac.uk/tobias-project/ as a place dedicated to hosting these URIs. By putting it at data.history.ac.uk rather than history.ac.uk, there was a clear separation between URIs and the pages of the website. For example, one of the URIs from the Tobias project was http://data.history.ac.uk/tobias-project/person/15601. While the format of the abovementioned URIs is the same as a URL, they do not link to web pages (try pasting it of them into a web browser). Many people new to LOD find this confusing. All URLs are URIs but not all URIs are URLs. A URI can describe anything at all, whereas URL describes the location of something on the web. So a URL tells you the location of a web page or a file or something similar. A URI just does the job of identifying something. Just as the International Standard Book Number, or ISBN 978-0-1-873354-6 uniquely identifies a hardback edition of Baptism, Brotherhood and Belief in Reformation Germany by Kat Hill, but doesn’t tell you where to get a copy. For that you would need something like a library shelfmark, which gives you an exact location on a shelf of a specific library.

There is a little bit of jargon around URIs. People talk about whether they are, or are not, dereferenceable. That just means can it be turned from an abstract reference into something else? For example, if you paste a URI into the address bar of a browser, will it return something? The VIAF URI for historian Simon Schama is:

http://viaf.org/viaf/46784579

If you put that into the browser you will get back a web page about Simon Schama which contains structured data about him and his publishing history. This is very handy - for one thing, it’s not obvious from the URI who or even what is being referred to. Similarly, if we treated a mobile phone number (with international code) as the URI for a person then it should be dereferenceable. Someone might answer the phone, and it might even be Schama.

But this is not essential. Lots of URIs are not dereferenceable, as in the example above from the Tobias project. You can’t find it anywhere; it is a convention.

The VIAF example leads us on to another important thing about URIs: don’t make them up unless you have to. People and organisations have been making concerted efforts to construct good URI lists and LOD isn’t going to work effectively if people duplicate that work by creating new URIs unnecessarily. For example VIAF has the support of many international libraries. If you want to construct URIs for people, VIAF is a very good choice. If you can’t find some people in VIAF, or other authority lists, only then might you need to make up your own.

How LOD organises knowledge: ontologies

It might not have been obvious from the individual triples we looked at in the opening section, but LOD can answer complex questions. When you put triples together then they form a graph, because of the way that the triples interlink. Suppose we want to find a list of all the people who were pupils of the composer Franz Liszt. If the information is in triples of linked data about pianists and their teachers, we can find out with a query (we’ll look at this query language, called SPARQL, in the final section).

For example, the pianist Charles Rosen was a pupil of the pianist Moriz Rosenthal, who was a pupil of Franz Liszt. Let’s now express that as two triples (we’ll just stick to strings for the names instead of ID numbers, to make the examples more readable):

"Franz Liszt" taughtPianoTo "Moriz Rosenthal" .

"Moriz Rosenthal" taughtPianoTo "Charles Rosen" .

We could equally have created our triples this way:

"Charles Rosen" wasTaughtPianoBy "Moriz Rosenthal" .

"Moriz Rosenthal" wasTaughtPianoBy "Franz Liszt" .

We’re making up examples simply for the purposes of illustration, but if you want to link your data to other datasets in the ‘linked data cloud’ you should look at what conventions are used in those datasets and do the same. Actually this is one of the most useful features of LOD because much of the work has been done for you. People have spent a lot of time developing ways of modelling information within a particular area of study and thinking about how relationships within that area can be represented. These models are generally known as ontologies. An ontology is an abstraction that allows particular knowledge about the world to be represented. Ontologies, in this sense, are quite new and they were designed to do what a hiearchical taxonomy does (think of the classification of species in the Linnaean system), but more flexibly.

An ontology is more flexible because it is non-hierarchical. It aims to represent the fluidity of the real world, where things can be related to each other in more complex ways than are represented by a hierarchical tree-like structure. Instead, an ontology is more like a spider’s web.

Whatever you are looking to represent with LOD, we suggest that you find an existing vocabulary and use it, rather than try to write your own. The main page here has a list of some of the most popular vocabularies.

Since our example above focuses on pianists, it would be a good idea to find an appropriate ontology rather than create our own system. In fact there is an ontology for music. As well as a well-developed specification it also has some useful examples of its use. You can have a look at the Getting started pages to get a sense of how you might use that particular ontology.

Unfortunately I can’t find anything that describes the relationship between a teacher and a pupil in the Music Ontology. But the ontology is published openly, so I can use it to describe other features of music and then create my own extension. If I then publish my extension openly, others can use it if they wish and it may become a standard. While the Music Ontology project does not have the relationship I need, the Linked Jazz project allows use of ‘mentorOf’, which sounds like it would work nicely in our case. While this is not an ideal solution, it is one that makes an effort to use what is already out there.

Now if you were studying the history of pianism you might want to identify many pianists who were taught by pupils of Liszt, to establish a kind of family tree and see if these ‘grandchildren’ of Liszt have something in common. You could research Liszt’s pupils, make a big list of them, and then research each of the pupils and try to make lists of any pupils they had. With LOD you could (again, if the triples exist) write a query along the lines of:

Give me the names of all pianists taught by x

where x was taught the piano by Liszt

This would return all of the people in the dataset who were pupils of pupils of Liszt. Let’s not get too excited: this query won’t give us every pupil of every pupil of Liszt that ever lived because that information probably doesn’t exist and doesn’t exist within any existing set of triples. Dealing with real-world data shows up all kind of omissions and inconsistencies, which we’ll see when we look at the biggest LOD set, DBpedia, in the final section.

If you have used relational databases you might be thinking that they can perform the same function. In our Liszt case, the information about pianists described above might be organised in a database table called something like ‘Pupils’.

| pupilID | teacherID |

|---|---|

| 31 | 17 |

| 35 | 17 |

| 49 | 28 |

| 56 | 28 |

| 72 | 40 |

If you’re not familiar with databases, don’t worry. But you can probably still see that some pianists in this table had the same teacher (numbers 17 and 28). Without going into details, if Liszt is in this database table it would be fairly easy to extract the pupils of pupils of Liszt, using a join.

Indeed, relational databases can offer similar results to LOD. The big difference is that LOD can go further: it can link datasets that were created with no explicit intention to link them together. The use of Resource Description Framework (RDF) and URIs allows this to happen.

RDF and data formats

LOD uses a standard, defined by the World Wide Web Consortium, or W3C, called Resource Description Framework, or just RDF. Standards are useful as long as they are widely adopted - think of the metre or standard screw sizes - even if they are essentially arbitrary. RDF has been widely adopted as the LOD standard.

You will often hear LOD referred to simply as RDF. We’ve delayed talking about RDF until now because it’s rather abstract. RDF is a data model that describes how data is structured on a theoretical level. So the insistence on using triples (rather than four parts, or two or nine, for example) is a rule in RDF. But when it comes to more practical matters you have some choices about implementation. So RDF tells you what you have to do but not exactly how you have to do it. These choices break down into two areas: how you write things down (serialisation) and the relationships your triples describe.

Serialisation

Serialisation is the technical term for ‘how you write things down’. Standard Chinese (Mandarin) can be written in traditional characters, simplified characters or Pinyin romanisation and the language itself doesn’t change. Similarly RDF can be written in various forms. Here we’ll look at two (there are others, but for simplicity’s sake, we will focus on these):

Recognising what serialisation you are looking at means that you can then choose appropriate tools designed for that format. For example, RDF can come serialised in XML format. You can then use a tool or code library designed for parsing that particular format, which is helpful if you already know how to work with it. Recognising the format also gives you the right keywords for searching online for help. Many resources offer their LOD databases for download and you may be able to choose which serialisation you want to download.

Turtle

‘Turtle’ is a play on words. ‘Tur’ is short for ‘terse’, and ‘tle’ - is short for ‘triple language’. Turtle is a pleasantly simple way of writing triples.

Turtle uses aliases or a shortcuts known as prefixes, which saves us having to write out full URIs every time. Let’s go back to the URI we invented in the previous section:

http://data.history.ac.uk/tobias-project/person/15601

We don’t want to type this out every time we refer to this person (Jack Straw, you’ll remember). So we just have to announce our shortcut:

@prefix toby: <http://data.history.ac.uk/tobias-project/person> .

Then Jack is toby:15601, which replaces the long URI and is easier on the eye. I have chosen ‘toby’, but could just as easily chosen any string of letters.

Let’s now move from Jack Straw to William Shakespeare and use Turtle to describe some stuff about his works. We’ll need to decide on the authority files to use, a process which, as mentioned above, is best gleaned from looking at other LOD sets. Here we’ll use Dublin Core, a library metadata standard, as one of our prefixes, the Library of Congress Control Number authority file for another, and the last one (VIAF) should be familiar to you. Together these three authority files provide unique identifiers for all of the entities I plan to use in this example.:

@prefix lccn: <http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names> .

@prefix dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/> .

@prefix viaf: <http://viaf.org/viaf> .

lccn:n82011242 dc:creator viaf:96994048 .

Note the spacing of the full point after the last line. This is Turtle’s way of indicating the end. You don’t technically have to have the space, but it does make it easier to read after a long string of characters.

In the above example, lccn:n82011242 represents Macbeth; dc:creator links Macbeth to its author; viaf:96994048 represents William Shakespeare.

Turtle also allows you to list triples without bothering to repeat each URI when you’ve only just used it. Let’s add the date when scholars think Macbeth was written, using the Dublin Core attribute-value pair: dc:created 'YYYY':

@prefix lccn: <http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names> .

@prefix dc: <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/> .

@prefix viaf: <http://viaf.org/viaf> .

lccn:n82011242 dc:creator viaf:96994048 ;

dc:created "1606" .

Remember the structure of the triple, discussed in section 1? There we gave this example:

1 person 15601 (the subject) 2 representedInUKParliament (the predicate) 3 "Blackburn" (the object)``

The key thing is that the predicate connects the subject and the object. It describes the relationship between them. The subject comes first in the triple, but that’s a matter of choice, as we discussed with the example of people who were taught the piano by Liszt.

You can use a semicolon if the subject is the same but the predicate and object are different, or a comma if the subject and predicate are the same and only the object is different.

lccn:no2010025398 dc:creator viaf:96994048 ,

viaf:12323361 .

Here we’re saying that Shakespeare (96994048) and John Fletcher (12323361) were both the creators of the work The Two Noble Kinsmen.

When we looked at ontologies earlier I suggested you have a look at the examples from the Music Ontology. I hope they didn’t put you off. Have a look again now. This is still complicated stuff, but do they make more sense now?

One of the most approachable ontologies is Friend of a Friend, or FOAF. This is designed to describe people, and is perhaps for that reason, fairly intuitive. If, for example, you want to write to tell me that this course is the best thing you’ve ever read, here is my email address expressed as triples in FOAF:

@prefix foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

:"Jonathan Blaney" foaf:mbox <mailto:jonathan.blaney@sas.ac.uk> .

RDF/XML

By contrast with Turtle, RDF/XML can look a bit weighty. To begin with, let’s just convert one triple from the Turtle above, the one that says that Shakespeare was the creator of The Two Noble Kinsmen:

lccn:no2010025398 dc:creator viaf:96994048 .

In RDF/XML, with the prefixes declared inside the XML snippet, this is:

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/terms/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/no2010025398">

<dc:creator rdf:resource="http://viaf.org/viaf/96994048"/>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>

The RDF/XML format has the same basic information as Turtle, but is written very differently, drawing on the principles of nested XML tags.

Let’s move on to a different example to show how RDF/XML combines triples and, at the same time, introduce Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS), which is designed for encoding thesauri or taxonomies.

<skosConcept rdf:about="http://www.ihr-tobias.org/concepts/21250/Abdication">

<skos:prefLabel>Abdication</skos:prefLabel>

</skosConcept>

Here we are saying that the SKOS concept 21250, abdication, has a preferred label of “abdication”. The way it works is that the subject element (including the abdication part, which is an attribute value in XML terms) has the predicate and object nested inside it. The nested element is the predicate and the leaf node, is the object. This example is taken from a project to publish a thesaurus of British and Irish History.

Just as with Turtle, we can add more triples. So let’s declare that the narrower term in our subject hierarchy, one down from Abdication is going to be Abdication crisis (1936).

<skosConcept rdf:about="http://www.ihr-tobias.org/concepts/21250/abdication">

<skos:prefLabel>Abdication</skos:prefLabel>

</skosConcept>

<skosConcept rdf:about="http://www.ihr-tobias.org/concepts/21250/abdication">

<skos:narrower rdf:resource="http://www.ihr-tobias.org/concepts/19838/abdication_crisis_1936"/>

</skosConcept>

Remember how predicates and objects are nested inside the subject? Here we’ve done that twice with the same subject, so we can make this less verbose by nesting both sets of predicates and objects inside the one subject:

<skosConcept rdf:about="http://www.ihr-tobias.org/concepts/21250/abdication">

<skos:prefLabel>Abdication</skos:prefLabel>

<skos:narrower rdf:resource="http://www.ihr-tobias.org/concepts/19838/abdication_crisis_1936"/>

</skosConcept>

If you’re familiar with XML this will be like mother’s milk to you. If you’re not you might prefer a format like Turtle. But the advantage here is that in creating my RDF/XML you can use the usual tools available with XML, like dedicated XML editors and parsers, to check that your RDF/XML is correctly formatted. If you’re not an XML person I recommend Turtle, for which you can use an online tool to check your syntax is correct.

Querying RDF with SPARQL

For this final section we will interrogate some LOD and see what you can do with it.

The query language we use for LOD is called SPARQL. It’s one of those recursive acronyms beloved of techie people: SPARQL Protocol and Query Language.

As I mentioned at the beginning, Programming Historian has a complete lesson, by Matthew Lincoln, on using SPARQL. My final section here is just an overview of the basic concepts, and if SPARQL piques your interest, you can get a thorough grounding from Lincoln’s tutorial.

We’re going to run our SPARQL queries on DBpedia, which is a huge LOD set derived from Wikipedia. As well as being full of information that is very difficult to find through the usual Wikipedia interface, it has several SPARQL “end points” - interfaces where you can type in SPARQL queries and get results from DBpedia’s triples.

The SPARQL query end point I use is called snorql. These end points occasionally seem to go offline, so if that should be the case, try searching for dbpedia sparql and you should find a similar replacement.

If you go to the snorql URL above you will see at first that a number of prefixes have already been declared for us, which is handy. You’ll recognise some of the prefixes now too.

snorql’s default query box, with some prefixes declared for you

In the query box below the prefix declarations you should see:

SELECT * WHERE {

...

}

If you’ve ever written a database query in Structured Query Language, better known as SQL, this will look pretty familiar and it will help you to learn SPARQL. If not, don’t worry. The keywords used here, SELECT and WHERE are not case sensitive, but some parts of a SPARQL query can be (see below), so I recommend that you stick to the given case throughout the queries in this course.

Here SELECT means return something and * means give me everything. WHERE introduces a condition, which is where we will put the details of what kinds of thing we want the query to return.

Let’s start with something simple to see how this works. Paste (or, better, type out) this into the query box:

SELECT * WHERE {

:Lyndal_Roper ?b ?c

}

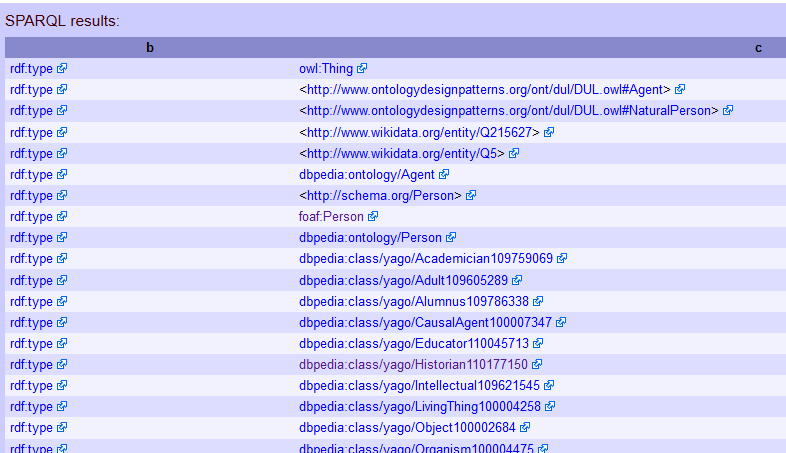

Hit ‘go’ and, if you left the drop-down box as ‘browse’ you should get two columns labelled “b” and “c”. (Note that here, searching for a string, case does matter: lyndal_roper will get you no results.)

top of results lists for a query for all triples with ‘Lyndal_Roper’ as subject

So what just happened? And how did I know what to type?

I didn’t, really, and that is one of the issues with SPARQL end points. When getting to know a dataset you have to try things and find out what terms are used. Because this comes from Wikipedia, and I was interested in what information on historians I could find, I went to the Wikipedia page for the historian Lyndal Roper.

The part at the end of the URL is Lyndal_Roper and I concluded that this string is likely to be how Roper is referred to in DBpedia. Because I don’t know what else might be in triples that mention Roper I use ?a and ?b: these are just place-holders: I could equally well have typed ?whatever and ?you_like and the columns would have had those headings. When you want to be more precise about what you are returning, it will be more important to label columns meaningfully.

Try your own SPARQL query now: choose a Wikipedia page and copy the end part of the URL, after the final slash, and put it in place of Lyndal_Roper. Then hit ‘go’.

From the information you get back from these results it’s possible to generate more precise queries. This can be a bit hit-and-miss, at least for me, so don’t worry if some don’t work.

Back to the results for the query I ran a moment ago:

SELECT * WHERE {

:Lyndal_Roper ?b ?c

}

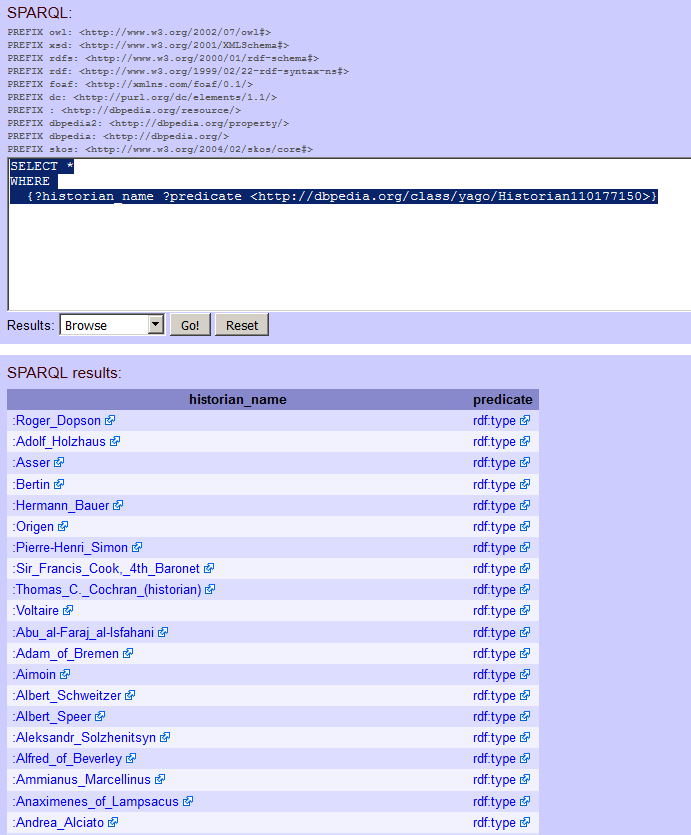

I can see a long list in the column labelled c. These are all the attributes Roper has in DBpedia and will help us to find other people with these attributes. For example I can see http://dbpedia.org/class/yago/Historian110177150. Can I use this to get a list of historians? I’m going to put this into my query but in third place (because that’s where it was when I found it in the Lyndal Roper results. My query looks like this:

SELECT * WHERE {

?historian_name ?predicate <http://dbpedia.org/class/yago/Historian110177150>

}

I’ve made a small change here. If this query works at all then I expect my historians to be in the first column, because ‘historian’ doesn’t look like it could be a predicate: it doesn’t function like a verb in a sentence; so I’m going to call my first results column ‘historian_name’ and my second (which I don’t know anything about) ‘predicate’.

Run the query. Does it work for you? I get a big list of historians.

historians, according to DBpedia

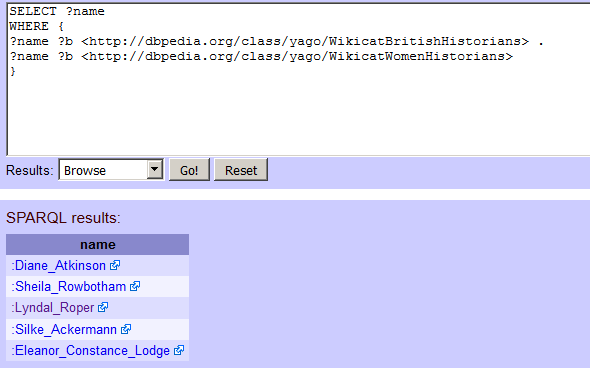

So this works for creating lists, which is useful, but it would much more powerful to combine lists, to get intersections of sests. I found a couple more things that might be interesting to query in Lyndal Roper’s DBpedia attributes: http://dbpedia.org/class/yago/WikicatBritishHistorians and http://dbpedia.org/class/yago/WikicatWomenHistorians. It’s very easy to combine these by asking a for a variable to be returned (in our case this is ?name) and then using that in multiple lines of a query. Note as well the space and full point at the end of the first line beginning with ?name:

SELECT ?name

WHERE {

?name ?b <http://dbpedia.org/class/yago/WikicatBritishHistorians> .

?name ?b <http://dbpedia.org/class/yago/WikicatWomenHistorians>

}

It works! I get five results. At the time of writing, there are five British, women historians in DBpedia…

British historians who are women, according to DBpedia

Only five British women historians? Of course there are, in reality, many more than that, as we could easily show by substituting the name of, say, Alison Weir in our first Lyndal Roper query. This brings us to the problem with Dbpedia that I mentioned earlier: it’s not very consistently marked up with structural information of the type DBpedia uses. Our query can list some British women historians but it turns out that we can’t use it to generate a meaningful list of people in this category. All we’ve found is the people in entries in Wikipedia that someone has decided to categorise as “British historian” and “woman historian”.

With SPARQL on DBpedia you have to be careful of the inconsistencies of crowd-sourced material. You could use SPARQL in exactly the same way on a more curated dataset, for example the UK government data: https://data-gov.tw.rpi.edu//sparql and expect to get more robust results (there is a brief tutorial for this dataset here: https://data-gov.tw.rpi.edu/wiki/A_crash_course_in_SPARQL).

However, despite its inconsistencies, DBpedia is a great place to learn SPARQL. This has only been an a brief introduction but there is much more in Using SPARQL to access Linked Open Data.

Further reading and resources

- Dean Allemang and James Hendler, Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist, 2nd edn, Elsevier, 2011

- Tim Berners-Lee Linked Data

- Bob DuCharme, Learning SPARQL, O’Reilly, 2011

- Bob DuCharme’s blog is also worth reading

- Richard Gartner, Metadata: Shaping Knowledge from Antiquity to the Semantic Web, Springer, 2016

- Seth van Hooland and Ruben Verborgh, Linked Data for Libraries, Archives and Museums, 2015

- Also see the book’s companion website

- Matthew Lincoln ‘Using SPARQL to access Linked Open Data’

- Linked Data guides and tutorials

- Dominic Oldman, Martin Doerr and Stefan Gradmann, ‘Zen and the Art of Linked Data: New Strategies for a Semantic Web of Humanist * Knowledge’, in A New Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by Susan Schreibman et al.

- Max Schmachtenberg, Christian Bizer and Heiko Paulheim, State of the LOD Cloud 2017

- David Wood, Marsha Zaidman and Luke Ruth, Linked Data: Structured data on the Web, Manning, 2014

Acknowlegements

I’d like to thank my two peer reviewers, Matthew Lincoln and Terhi Nurmikko-Fuller, and my editor, Adam Crymble, for generously spending time helping me to improve this course with numerous suggestions, clarification and corrections. This tutorial is based on one written as part of the ‘Thesaurus of British and Irish History as SKOS’ (Tobias) project, funded by the AHRC. It has been revised for the Programming Historian.