Contents

- Module Goals

- For Whom is this Useful?

- Applying our Historical Knowledge

- The Advanced Search on OBO

- Understanding URL Queries

- Systematically Downloading Files

- Further Reading

Module Goals

Downloading a single record from a website is easy, but downloading many records at a time – an increasingly frequent need for a historian – is much more efficient using a programming language such as Python. In this lesson, we will write a program that will download a series of records from the Old Bailey Online using custom search criteria, and save them to a directory on our computer. This process involves interpreting and manipulating URL Query Strings. In this case, the tutorial will seek to download sources that contain references to people of African descent that were published in the Old Bailey Proceedings between 1700 and 1750.

For Whom is this Useful?

Automating the process of downloading records from an online database will be useful for anyone who works with historical sources that are stored online in an orderly and accessible fashion and who wishes to save copies of those sources on their own computer. It is particularly useful for someone who wants to download many specific records, rather than just a handful. If you want to download all or most of the records in a particular database, you may find Ian Milligan’s tutorial on Automated Downloading with WGET more suitable.

The present tutorial will allow you to download discriminately, isolating specific records that meet your needs. Downloading multiple sources automatically saves considerable time. What you do with the downloaded sources depends on your research goals. You may wish to create visualizations or perform various data analysis methods, or simply reformat them to make browsing easier. Or, you may just want to keep a backup copy so you can access them without Internet access.

This lesson is for intermediate Python users. If you have not already tried the Python Programming Basics lessons, you may find that a useful starting point.

Applying our Historical Knowledge

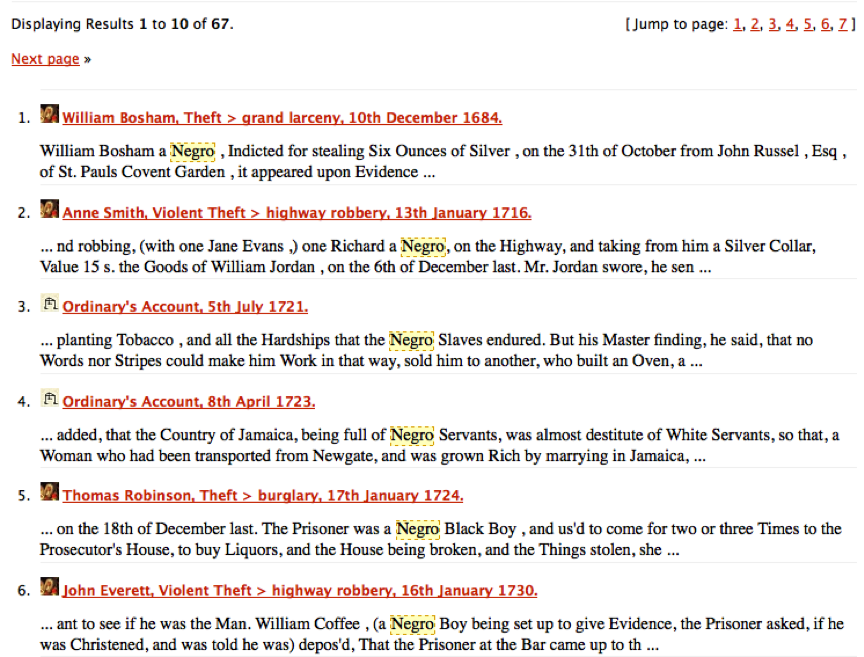

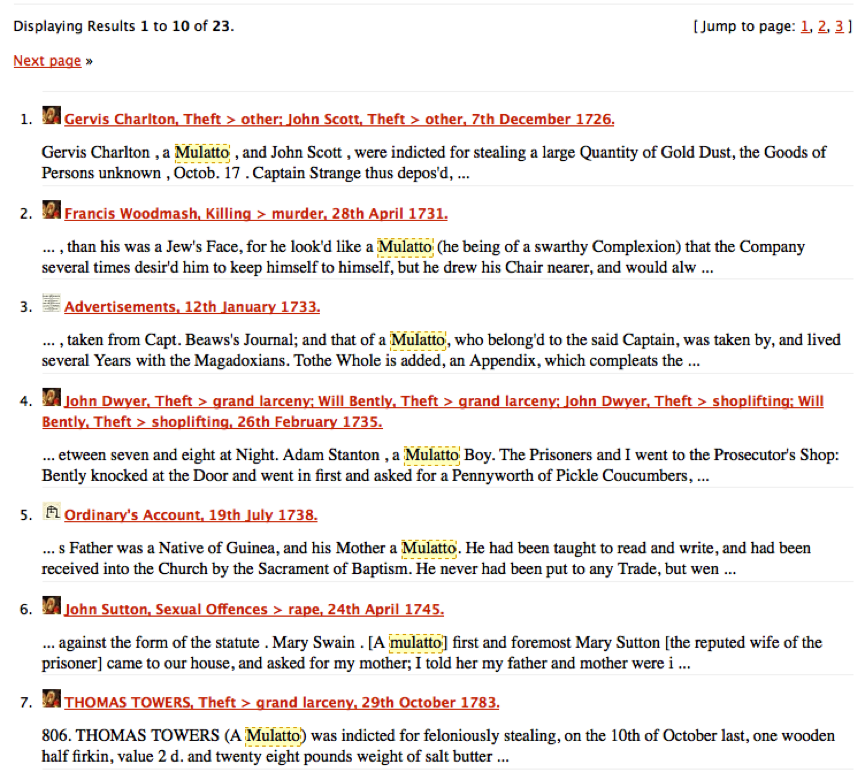

In this lesson, we are trying to create our own corpus of cases related to people of African descent. From Benjamin Bowsey’s case at the Old Bailey in 1780, we might note that “black” can be a useful keyword for us to use for locating other cases involving defendants of African descent. However, when we search for “black” on the Old Bailey website, we find it often refers to other uses of the word: black horses, or black cloth. The task of disambiguating this use of language will have to wait for another lesson. For now, let’s turn to easier cases. As historians, we can probably think of keywords of historic racialised terms related to African descendants that would be worth pursuing. The infamous “n-word” of course is not useful, as this term did not come into regular usage until the mid-nineteenth century. Other racialised language such as “negro” and “mulatto” are however, much more relevant to the early eighteenth century. These keywords are less ambiguous than “black” and are much more likely to be immediate references to people in our target demographic. If we try these two terms in separate simple searches on the Old Bailey website, we get results like in these screenshots:

Search results for ‘negro’ in the Old Bailey Online

Search results for ‘mulatto’ in the Old Bailey Online

After glancing through these search results, it seems clear that these are references to people, rather than horses or cloth or other things that may be black. We want to download them all to use in our analysis. We could, of course, download them one at a time, manually. But let’s find a programmatic way to automate this task.

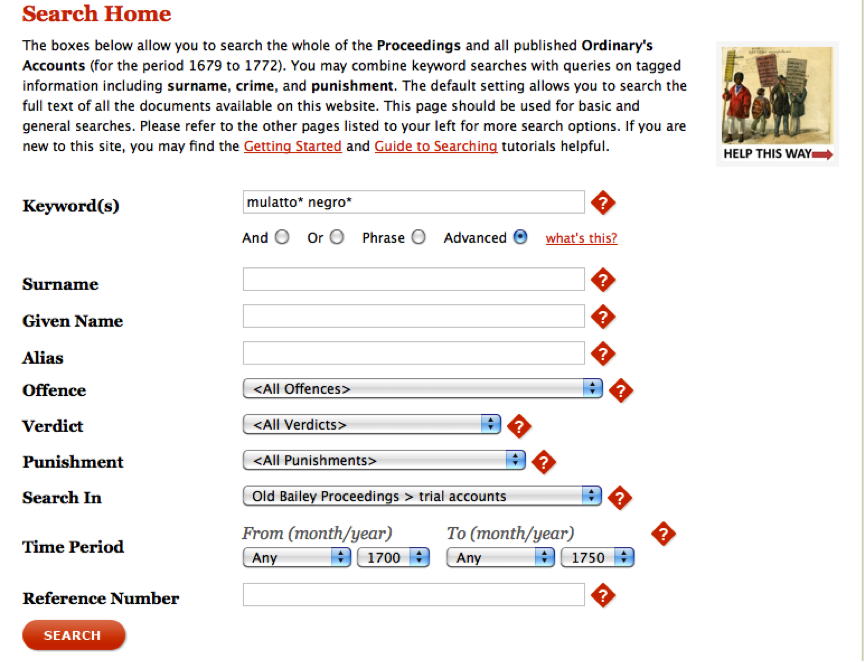

The Advanced Search on OBO

Every website’s search features work differently. While searches work

similarly, the intricacies of database searches may not be entirely

obvious. Therefore it’s important to think critically about database

search options and, when available, read the documentation provided on

the website. Prudent historical researchers always interrogate their

sources; the procedures behind your search boxes should receive the same

attention. The Old Bailey Online’s advanced search form lets you

refine your searches based on ten different fields including simple

keywords, a date range, and a crime type. As each website’s search

feature is different it always pays to take a moment or two to play with

and read about the search options available. Since

we have already done the simple searches for “negro” and “mulatto”, we

know there will be results. However, let’s use the advanced search to

limit our results to records published in the Old Bailey Proceedings

trial accounts from 1700 to 1750 only. You can of course change this to

whatever you like, but this will make the example easier to follow.

Perform the search shown in the image below. Make sure you tick the

“Advanced” radio button and include the * wildcards to include

pluralized entries or those with an extra “e” on the end.

Old Bailey Advanced Search Example

Execute the search and then click on the “Calculate Total” link to see how many entries there are. We now have 13 results (if you have a different number go back and make sure you copied the example above exactly). What we want to do at this point is download all of these trial documents and analyze them further. Again, for only 13 records, you might as well download each record manually. But as more and more data comes online, it becomes more common to need to download 1,300 or even 130,000 records, in which case downloading individual records becomes impractical and an understanding of how to automate the process becomes that much more valuable. To automate the download process, we need to step back and learn how the search URLs are created on the Old Bailey website, a method common to many online databases and websites.

Understanding URL Queries

Take a look at the URL produced with the last search results page. It should look like this:

https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_divs_fulltext=mulatto*+negro*&kwparse=advanced&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount&fromYear=1700&fromMonth=00&toYear=1750&toMonth=99&start=0&count=0

We had a look at URLs in Viewing HTML Files, but this looks a lot more complex. Although longer, it is actually not that much more complex. But it is easier to understand by noticing how our search criteria get represented in the URL.

https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp

?gen=1

&form=searchHomePage

&_divs_fulltext=mulatto*+negro*

&kwparse=advanced

&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount

&fromYear=1700

&fromMonth=00

&toYear=1750

&toMonth=99

&start=0

&count=0

In this view, we see more clearly our 12 important pieces of information

that we need to perform our search (one per line). On the first is the

Old Bailey’s base website URL, followed by a query: “?” (don’t worry

about the gen=1 bit; the developers of the Old Bailey Online say that

it does not do anything.) and a series of 10 name/value pairs put

together with & characters. Together these 10 name/value pairs comprise

the query string, which tells the search engine what variables to use in

specific stages of the search. Notice that each name/value pair contains

both a variable name: toYear, and then assigns that variable a value: 1750.

This works in exactly the same way as Function Arguments by

passing certain information to specific variables. In this case, the

most important variable is _divs_fulltext= which has been given the

value:

mulatto*+negro*

This holds the search term we have typed into the search box. The program has automatically added a + sign in place of a blank space (URLs cannot contain spaces); otherwise that’s exactly what we’ve asked the Old Bailey site to find for us. The other variables hold values that we defined as well. fromYear and toYear contain our date range. Since no year has 99 months as suggested in the toMonth variable, we can assume this is how the search algorithm ensures all records from that year are included. There are no hard and fast rules for figuring out what each variable does because the person who built the site gets to name them. Often you can make an educated guess. All of the possible search fields on the Advanced Search page have their own name/value pair. If you’d like to find out the name of the variable so you can use it, do a new search and make sure you put a value in the field in which you are interested. After you submit your search, you’ll see your value and the name associated with it as part of the URL of the search results page. With the Old Bailey Online, as with many other websites, the search form (advanced or not) essentially helps you to construct URLs that tell the database what to search for. If you can understand how the search fields are represented in the URL – which is often quite straightforward – then it becomes relatively simple to programmatically construct these URLs and thus to automate the process of downloading records.

Now try changing the “start=0” to “start=10” and hit enter. You should now have results 11-13. The “start” variable tells the website which entry should be shown at the top of the search results list. We should be able to use this knowledge to create a series of URLs that will allow us to download all 13 files. Let’s turn to that now.

Systematically Downloading Files

In Working with Webpages we learned that Python can download a webpage as long as we have the URL. In that lesson we used the URL to download the trial transcript of Benjamin Bowsey. In this case, we’re trying to download multiple trial transcripts that meet the search criteria we outlined above without having to repeatedly re-run the program. Instead, we want a program that will download everything we need in one go. At this point we have a URL to a search results page that contains the first ten entries of our search. We also know that by changing the “start” value in the URL we can sequentially call each search results page, and ultimately retrieve all of the trial documents from them. Of course the research results don’t give us the trial documents themselves, but only links to them. So we need to extract the link to the underlying records from the search results. On the Old Bailey Online website, the URLs for the individual records (the trial transcript files) can be found as links on the search results pages. We know that all trial transcript URLs contain a trial id that takes the form: “t” followed by at least 8 numbers (e.g. t17800628-33). By looking for links that contain that pattern, we can identify trial transcript URLs. As in previous lessons, let’s develop an algorithm so that we can begin tackling this problem in a manner that a computer can handle. It seems this task can be achieved in four steps. We will need to:

- Generate the URLs for each search results page by incrementing the “start” variable by a fixed amount an appropriate number of times.

- Download each search results page as an HTML file.

- Extract the URLs of each trial transcript (using the trial ID as described above) from the search results HTML files.

- Cycle through those extracted URLs to download each trial transcript and save it to a directory on our computer

You’ll recall that this is fairly similar to the tasks we achieved in Working with Webpages and From HTML to a List of Words 2. First we download, then we parse out the information we’re after. And in this case, we download some more.

Downloading the search results pages

First we need to generate the URLs for downloading each search results page. We have already got the first one by using the form on the website:

https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_divs_fulltext=mulatto*+negro*&kwparse=advanced&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount&fromYear=1700&fromMonth=00&toYear=1750&toMonth=99&start=0&count=0

We could type this URL out twice and alter the ‘start’ variable to get

us all 13 entries, but let’s write a program that would work no matter

how many search results pages or records we had to download, and no

matter what we decide to search for. Study this code and then add this

function to a module named obo.py (create a file with that name and save it to the directory where you want to do your work). The comments in the code are meant to

help you decipher the various parts.

# obo.py

def getSearchResults(query, kwparse, fromYear, fromMonth, toYear, toMonth):

import urllib.request

startValue = 0

#each part of the URL. Split up to be easier to read.

url = 'https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_divs_fulltext='

url += query

url += '&kwparse=' + kwparse

url += '&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount'

url += '&fromYear=' + fromYear

url += '&fromMonth=' + fromMonth

url += '&toYear=' + toYear

url += '&toMonth=' + toMonth

url += '&start=' + str(startValue)

url += '&count=0'

#download the page and save the result.

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

filename = 'search-result'

f = open(filename + ".html", 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

In this function we have split up the various Query String components

and used Function Arguments so that this function can be reused beyond

our specific needs right now. When we call this function we will replace

the arguments with the values we want to search for. We then download

the search results page in a similar manner as done in Working with

Webpages. Now, make a new file: download-searches.py and copy into

it the following code. Note, the values we have passed as arguments are

exactly the same as those used in the example above. Feel free to play

with these to get different results or see how they work.

#download-searches.py

import obo

query = 'mulatto*+negro*'

obo.getSearchResults(query, "advanced", "1700", "00", "1750", "99")

When you run this code you should find a new file:

“search-results.html” in your programming-historian directory

containing the first search results page for your search. Check that

this downloaded properly and then delete the file. We’re going to adapt

our program to download the other page containing the other 3 entries at

the same time so we want to make sure we get both. Let’s refine our

getSearchResults function by adding another function argument called

“entries” so we can tell the program how many pages of search results we

need to download. We will use the value of entries and some simple math

to determine how many search results pages there are. This is fairly

straightforward since we know there are ten trial transcripts listed per

page. We can calculate the number of search results pages by dividing

the value of entries by 10. We will save this result to a

variable named pageCount. It looks like this:

#determine how many files need to be downloaded.

pageCount = entries / 10

However, in cases where the number of entries is not a multiple of 10,

this will result in a decimal number. You can test this by

running this code in your Terminal (Mac & Linux) / Python Command Line

(Windows) and printing out the value held in pageCount. (Note, from here

on, we will use the word Terminal to refer to this program).

entries = 13

pageCount = entries / 10

print(pageCount)

-> 1.3

We know the page count should be 2 (one page containing entries 1-10, and one page containing entries 11-13). Since we always want the next higher integer, we can round up the result of the division.

#determine how many files need to be downloaded.

import math

pageCount = entries / 10

pageCount = math.ceil(pageCount)

If we add this to our getSearchResults function just under the

startValue = 0 line, our program, the code can now calculate the number

of pages that need to be downloaded. However, at this stage it will

still only download the first page since we have only told the

downloading section of the function to run once. To correct this, we can

add that downloading code to a for loop which will download once for

every number in the pageCount variable. If it reads 1, then it will

download once; if it reads 5 it will download five times, and so on.

Immediately after the if statement you have just written, add the

following line and indent everything down to f.close one additional

tab so that it is all enclosed in the for loop:

for pages in range(1, pageCount+1):

print(pages)

Since this is a for loop, all of the code we want to run repeatedly

needs to be intended as well. You can see if you have done this

correctly by looking at the finished code example below. This loop takes

advantage of Python’s range funciton. To understand this for loop it

is probably best to think of pageCount as equal to 2 as it is in the

example. This two lines of code then means: start running with an

initial loop value of 1, and each time you run, add 1 more to that

value. When the loop value is the same as pageCount, run once more and

then stop. This is particularly valuable for us because it means we can

tell our program to run exactly once for each search results page and

provides a flexible new skill for controlling how many times a for loop

runs. If you would like to practice with this new and powerful way of

writing for loops, you can open your Terminal and play around.

pageCount = 2

for pages in range(1, pageCount+1):

print(pages)

-> 1

-> 2

Before we add all of this code together to our getSearchResults

function, we have to make two final adjustments. At the end of the for

loop (but still inside the loop), and after our downloading code has run

we will need to change the startValue variable, which is used in

building the URL of the page we want to download. If we forget to do

this, our program will repeatedly download the first search results page

since we are not actually changing anything in the initial URL. The

startValue variable, as discussed above, is what controls which search

results page we want to download. Therefore, we can request the next

search results page by increasing the value of startValue by 10 after

the initial download has completed. If you are not sure where to put

this line you can peek ahead to the finished code example below.

Finally, we want to ensure that the name of the file we have downloaded

is different for each file. Otherwise, each download will save over the

previous download, leaving us with only a single file of search results.

To solve this, we can adjust the contents of the filename variable to

include the value held in startValue so that each time we download a new

page, it gets a different name. Since startValue is an integer, we will

have to convert it to a string before we can add it to the filename

variable. Adjust the line in your program that pertains to the filename

variable to looks like this:

filename = 'search-result' + str(startValue)

You should now be able to add these new lines of code to your getSearchResults function. Recall we have made the following additions:

- Add entries as an additional function argument right after toMonth

- Calculate the number of search results pages and add this immediately after the line that begins with startValue = 0 (before we build the URL and start downloading)

- Follow this immediately with a for loop that will tell the program to run once for each search results page, and indent the rest of the code in the function so that it is inside the new loop.

- The last line in the for loop should now increase the value of the startValue variable each time the loop runs.

- Adjust the existing filename variable so that each time a search results page is downloaded it gives the file a unique name.

The finished function code in your obo.py file should look like this:

#create URLs for search results pages and save the files

def getSearchResults(query, kwparse, fromYear, fromMonth, toYear, toMonth, entries):

import urllib.request, math

startValue = 0

#this is new! Determine how many files need to be downloaded.

pageCount = entries / 10

pageCount = math.ceil(pageCount)

#this line is new!

for pages in range(1, pageCount +1):

#each part of the URL. Split up to be easier to read.

url = 'https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_divs_fulltext='

url += query

url += '&kwparse=' + kwparse

url += '&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount'

url += '&fromYear=' + fromYear

url += '&fromMonth=' + fromMonth

url += '&toYear=' + toYear

url += '&toMonth=' + toMonth

url += '&start=' + str(startValue)

url += '&count=0'

#download the page and save the result.

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

filename = 'search-result' + str(startValue)

f = open(filename + ".html", 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

#this lines is new!

startValue = startValue + 10

To run this new function, add the extra argument to

download-searches.py and run the program again:

#download-searches.py

import obo

query = 'mulatto*+negro*'

obo.getSearchResults(query, "advanced", "1700", "00", "1750", "99", 13)

Great! Now we have both search results pages, called

search-result0.html and search-result10.html. But before we move

onto the next step in the algorithm, let’s take care of some

housekeeping. Our programming-historian directory will quickly become

unwieldy if we download multiple search results pages and trial

transcripts. Let’s have Python make a new directory named after our

search terms.

We want to add this new functionality in getSearchResults, so that our

search results pages are downloaded to a directory with the same name as

our search query. This will keep our programming-historian directory

more organized. To do this we will create a new directory using the os

library, short for “operating system”. That library contains a function

called makedirs, which, unsurprisingly, makes a new directory. You can

try this out using the Terminal.

import os

query = "myNewDirectory"

if not os.path.exists(query):

os.makedirs(query)

This program will check to see if your computer already has a directory

with this name. If not, you should now have a directory called

myNewDirectory on your computer. On a Mac this is probably located in

your /Users/username/ directory, and on Windows you should be able to

find it in the Python directory on your computer, the same in which

you opened your command line program. If this worked you can delete the

directory from your hard drive, since it was just for practice. Since we

want to create a new directory named after the query that we input into

the Old Bailey Online website, we will make direct use of the query

function argument from the getSearchResults function. To do this, import

the os library after the others and then add the

code you have just written immediately below. Your getSearchResults

function should now look like this:

#create URLs for search results pages and save the files

def getSearchResults(query, kwparse, fromYear, fromMonth, toYear, toMonth, entries):

import urllib.request, math, os

#This line is new! Create a new directory

if not os.path.exists(query):

os.makedirs(query)

startValue = 0

#Determine how many files need to be downloaded.

pageCount = entries / 10

pageCount = math.ceil(pageCount)

for pages in range(1, pageCount +1):

#each part of the URL. Split up to be easier to read.

url = 'https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_divs_fulltext='

url += query

url += '&kwparse=' + kwparse

url += '&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount'

url += '&fromYear=' + fromYear

url += '&fromMonth=' + fromMonth

url += '&toYear=' + toYear

url += '&toMonth=' + toMonth

url += '&start=' + str(startValue)

url += '&count=0'

#download the page and save the result.

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

#save the result to the new directory

filename = 'search-result' + str(startValue)

f = open(filename + ".html", 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

startValue = startValue + 10

The last step for this function is to make sure that when we save our search results pages, we save them in this new directory. To do this we can make a minor adjustment to the filename variable so that the file ends up in the right place. There are many ways we can do this, the easiest of which is just to append the new directory name plus a slash to the name of the file:

filename = query + '/' + 'search-result' + str(startValue)

If your computer is running Windows you will need to use a backslash

instead of a forward slash in the above example. Add the above line to

your getSearchResults page in lieu of the current filename description.

If you are running Windows, chances are your downloadSearches.py

program will now crash when you run it because you are trying to create

a directory with a * in it. Windows does not like this. To get around

this problem we can use regular expressions to remove any

non-Windows-friendly characters. We used regular expressions previously

in Counting Frequencies. To remove non-alpha-numeric characters from

the query, first import the regular expressions library immediately

after you have imported the os library, then use the re.sub() function

to create a new string named cleanQuery that contains only alphanumeric

characters. You will then have to substitute cleanQuery as the variable

used in the os.path.exists(), os.makedirs(), and filename declarations.

import urllib.request, math, os, re

cleanQuery = re.sub(r'\W+', '', query)

if not os.path.exists(cleanQuery):

os.makedirs(cleanQuery)

...

filename = cleanQuery + '/' + 'search-result' + str(startValue)

The final version of your function should look like this:

#create URLs for search results pages and save the files

def getSearchResults(query, kwparse, fromYear, fromMonth, toYear, toMonth, entries):

import urllib.request, math, os, re

cleanQuery = re.sub(r'\W+', '', query)

if not os.path.exists(cleanQuery):

os.makedirs(cleanQuery)

startValue = 0

# Determine how many files need to be downloaded.

pageCount = entries / 10

pageCount = math.ceil(pageCount)

for pages in range(1, pageCount +1):

#each part of the URL. Split up to be easier to read.

url = 'https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_divs_fulltext='

url += query

url += '&kwparse=' + kwparse

url += '&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount'

url += '&fromYear=' + fromYear

url += '&fromMonth=' + fromMonth

url += '&toYear=' + toYear

url += '&toMonth=' + toMonth

url += '&start=' + str(startValue)

url += '&count=0'

#download the page and save the result.

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

filename = cleanQuery + '/' + 'search-result' + str(startValue)

f = open(filename + ".html", 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

startValue = startValue + 10

This time we tell the program to download the trials and put them in the

new directory rather than our programming-historian directory. Run

download-searches.py once more to ensure this worked and you

understand how to save files to a particular directory using Python.

Downloading the individual trial entries

At this stage we have created a function that can download all of the search results HTML files from the Old Bailey Online website for an advanced search that we have defined, and have done so programmatically. Now for the next step in the algorithm: Extract the URLs of each trial transcript from the search results HTML files. In the lessons that precede this one (eg, Working with Webpages), we have worked with the printer friendly versions of the trial transcripts, so we will continue to do so. We know that the printer friendly version of Benjamin Bowsey’s trial is located at the URL:

http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/print.jsp?div=t17800628-33

In the same way that changing query strings in the URLs yields different

search results, changing the URL for trial records – namely substituting

one trial ID for another – we will get the transcript for that new

trial. This means that to find and download the 13 matching files, all

we need are these trial IDs. Since we know that search results pages on

websites generally contain a link to the pages described, there is a

good chance that we can find these links embedded in the HTML code. If

we can scrape this information from the downloaded search results pages,

we can then use that information to generate a URL that will allow us to

download each trial transcript. This is a technique that you can use for

most search result pages, not just Old Bailey Online! To do this, we

must first find where the trial IDs are amidst the HTML code in the

downloaded files, and then determine a way to consistently isolate them

using code so that no matter which search results page we download from

the site we are able to find the trial transcripts. First, open

search-results0.html in Komodo Edit and have a look for the list of

the trials. The first entry starts with “Anne Smith” so you can use the

“find” feature in Komodo Edit to jump immediately to the right spot.

Notice Anne’s name is part of a link:

browse.jsp?id=t17160113-18&div=t17160113-18&terms=mulatto*_negro*#highlight

Perfect, the link contains the trial ID! Scroll through the remaining

entries and you’ll find the same is true. Lucky for us, the site is well

formatted and it looks like each link starts with “browse.jsp?id=”

followed by the trial ID and finished with an &, in Anne’s case:

“browse.jsp?id=t17160113-18&”. We can write a few lines of code that can

isolate those IDs. Take a look at the following function. This function

also uses the os library, in this case to list all of the files

located in the directory created in the previous section. The os

library contains a range of useful functions that mirror the types of

tasks you would expect to be able to do with your mouse in the Mac

Finder or Windows such as opening, closing, creating, deleting, and

moving files and directories, and is a great library to master – or at

least familiarize yourself with.

def getIndivTrials(query):

import os, re

cleanQuery = re.sub(r'\W+', '', query)

searchResults = os.listdir(cleanQuery)

print(searchResults)

Create and run a new program called extract-trial-ids.py with the

following code. Make sure you input the same value into the query

argument as you did in the previous example:

import obo

obo.getIndivTrials("mulatto*+negro*")

If everything went right, you should see a list containing the names of all the files in your new “mulatto*+negro*” directory, which at this point should be the two search results pages. Ensure this worked before moving forward. Since we saved all of the search results pages with a filename that includes “search-results”, we now want to open each file with a name containing “search-results”, and extract all trial IDs found therein. In this case we know we have 2, but we want our code to be as reusable as possible (with reason, of course!) Restricting this action to files named “search-results” will mean that this program will work as intended even if the directory contains many other unrelated files because the program will skip over anything with a different name. Add the following to your getIndivTrials() function, which will check if each file contains “search-results” in its name. If it does, the file will be opened and the contents saved to a variable named text. That text variable will then be parsed looking for the trial ID, which we know always follows “browse.jsp?id=”. If and when that trial ID is found it will be saved to a list and printed to the command output, which leaves us with all of the information we need to then write a program that will download the desired trials.

def getIndivTrials(query):

import os, re

cleanQuery = re.sub(r'\W+', '', query)

searchResults = os.listdir(cleanQuery)

urls = []

#find search-results pages

for files in searchResults:

if files.find("search-result") != -1:

f = open(cleanQuery + "/" + files, 'r')

text = f.read().split(" ")

f.close()

#look for trial IDs

for words in text:

if words.find("browse.jsp?id=") != -1:

#isolate the id

urls.append(words[words.find("id=") +3: words.find("&")])

print(urls)

That last line of the for loop may look tricky, but make sure you understand it before moving on. The words variable is checked to see if it contains the characters “id=” (without the quotes), which of course refers to a specific trial transcript ID. If it does, we use the slice string method to capture only the chunk between id= and & and append it to the url list. If we knew the exact index positions of this substring we could have used those numerical values instead. However, by using the find() string method we have created a much more flexible program. The following code does exactly the same thing as that last line in a less condensed manner.

idStart = words.find("id=") + 3

idEnd = words.find("&")

trialID = words[idStart: idEnd]

urls.append(trialID)

When you re-run extract-trial-ids.py, you should now see a list of all

the trial IDs. We can add a couple extra lines to turn these into proper

URLs and download the whole list to our new directory. We’ll also use

the time library to pause our program for three seconds between

downloads– a technique called throttling. It’s considered good form not

to pound someone’s server with many requests per second; and the slight

delay makes it more likely that all the files will actually download

rather than time out. Add the following code to the end of your

getIndivTrials() function. This code will generate the URL of each

individual page, download the page to your computer, place it in your

new directory, save the file, and pause for 3 seconds before moving on

to the next trial. This work is all contained in a for loop, and will

run once for every trial in your url list.

def getIndivTrials(query):

#...

import urllib.request, time

#import built-in python functions for building file paths

from os.path import join as pjoin

for items in urls:

#generate the URL

url = "http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/print.jsp?div=" + items

#download the page

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

#create the filename and place it in the new directory

filename = items + '.html'

filePath = pjoin(cleanQuery, filename)

#save the file

f = open(filePath, 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

#pause for 3 second

time.sleep(3)

If we put this all together into a single function it should look something like this. (Note, we’ve put all the “import” calls at the top to keep things cleaner).

def getIndivTrials(query):

import os, re, urllib.request, time

#import built-in python functions for building file paths

from os.path import join as pjoin

cleanQuery = re.sub(r'\W+', '', query)

searchResults = os.listdir(cleanQuery)

urls = []

#find search-results pages

for files in searchResults:

if files.find("search-result") != -1:

f = open(cleanQuery + "/" + files, 'r')

text = f.read().split(" ")

f.close()

#look for trial IDs

for words in text:

if words.find("browse.jsp?id=") != -1:

#isolate the id

urls.append(words[words.find("id=") +3: words.find("&")])

#new from here down!

for items in urls:

#generate the URL

url = "http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/print.jsp?div=" + items

#download the page

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

#create the filename and place it in the new directory

filename = items + '.html'

filePath = pjoin(cleanQuery, filename)

#save the file

f = open(filePath, 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

#pause for 3 seconds

time.sleep(3)

Let’s add the same three-second pause to our getSearchResults function

to be kind to the Old Bailey Online servers:

#create URLs for search results pages and save the files

def getSearchResults(query, kwparse, fromYear, fromMonth, toYear, toMonth, entries):

import urllib.request, math, os, re, time

cleanQuery = re.sub(r'\W+', '', query)

if not os.path.exists(cleanQuery):

os.makedirs(cleanQuery)

startValue = 0

#Determine how many files need to be downloaded.

pageCount = entries / 10

pageCount = math.ceil(pageCount)

for pages in range(1, pageCount +1):

#each part of the URL. Split up to be easier to read.

url = 'https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_divs_fulltext='

url += query

url += '&kwparse=' + kwparse

url += '&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount'

url += '&fromYear=' + fromYear

url += '&fromMonth=' + fromMonth

url += '&toYear=' + toYear

url += '&toMonth=' + toMonth

url += '&start=' + str(startValue)

url += '&count=0'

#download the page and save the result.

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

filename = cleanQuery + '/' + 'search-result' + str(startValue)

f = open(filename + ".html", 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

startValue = startValue + 10

#pause for 3 seconds

time.sleep(3)

Finally, call the function in the download-searches.py program.

#download-searches.py

import obo

query = 'mulatto*+negro*'

obo.getSearchResults(query, "advanced", "1700", "00", "1750", "99", 13)

obo.getIndivTrials(query)

Now, you’ve created a program that can request and download files from the Old Bailey website based on search parameters you define, all without visiting the site!

In case a file does not download

Check to make all thirteen files have downloaded properly. If that’s the case for you, that’s great! However, there’s a possibility that this program stalled along the way. That’s because our program, though running on your own machine, relies on two factors outside of our immediate control: the speed of the Internet, and the response time of the Old Bailey Online server at that moment. It’s one thing to ask Python to download a single file, but when we start asking for a file every 3 seconds there’s a greater chance the server will either time out or fail to send us the file we are after.

If we were using a web browser to make these requests, we’d eventually get a message that the “connection had timed out” or something of the sort. We all see this from time to time. However, our program isn’t built to handle or relay such error messages, so instead you’ll realize it when you discover that the program has not returned the expected number of files or just seemingly does nothing. To prevent frustration and uncertainty, we want a fail-safe in our program that will attempt to download each trial. If for whatever reason it fails, we’ll make a note of it and move on to the next trial.

To do this, we will make use of the Python try / except error

handling mechanism, as well as a new library: socket. Try and Except are

a lot like an if / else statement. When you ask Python to try something,

it will attempt to run the code; if the code fails to achieve what you

have defined, it will run the except code. This is often used when

dealing with errors, known as error handling. We can use this to our

advantage by telling our program to attempt downloading a page. If it

fails, we’ll ask it to let us know which file failed and then move on.

To do this we need to use the socket library, which will allow us to put

a time limit on a download attempt before moving on. This involves

altering the getIndivTrials function.

First, we need to load the socket library, which should be done in the

same way as all of our previous library imports. Then, we need to import

the urllib.error library, which allows us to handle download errors.

We will also need to

set the default socket timeout length – how long do we want to try to

download a page before we give up. This should go immediately after the

comment that begins with #download the page

import os, re, urllib.request, urllib.error, time, socket

#...

#download the page

socket.setdefaulttimeout(10)

Then, we need a new python list that will hold all of the urls that

failed to download. We will call this failedAttempts and you can insert

it immediately after the import instructions:

failedAttempts = []

Finally, we can add the try / except statement, which is added in much

the same way as an if / else statement would be. In this case, we will

put all of the code designed to download and save the trials in the try

statement, and in the except statement we will tell the program what we

want it to do if that should fail. Here, we will append the url that

failed to download to our new list, failedAttempts

#...

socket.setdefaulttimeout(10)

try:

response = urllib2.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

#create the filename and place it in the new "trials" directory

filename = items + '.html'

filePath = pjoin(newDir, filename)

#save the file

f = open(filePath, 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

except urllib.error.URLError:

failedAttempts.append(url)

Finally, we will tell the program to print the contents of the list to the command output so we know which files failed to download. This should be added as the last line in the function.

print("failed to download: " + str(failedAttempts))

Now when you run the program, should there be a problem downloading a

particular file, you will receive a message in the Command Output window

of Komodo Edit. This message will contain any URLs of files that failed

to download. If there are only one or two, it’s probably fastest just to

visit the pages manually and use the “Save As” feature of your browser.

If you are feeling adventurous, you could modify the program to

automatically download the remaining files. The final version of your

getSearchResults() and getIndivTrials() functions should now

look like this:

#create URLs for search results pages and save the files

def getSearchResults(query, kwparse, fromYear, fromMonth, toYear, toMonth, entries):

import urllib.request, math, os, re, time

cleanQuery = re.sub(r'\W+', '', query)

if not os.path.exists(cleanQuery):

os.makedirs(cleanQuery)

startValue = 0

#Determine how many files need to be downloaded.

pageCount = entries / 10

pageCount = math.ceil(pageCount)

for pages in range(1, pageCount +1):

#each part of the URL. Split up to be easier to read.

url = 'https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/search.jsp?gen=1&form=searchHomePage&_divs_fulltext='

url += query

url += '&kwparse=' + kwparse

url += '&_divs_div0Type_div1Type=sessionsPaper_trialAccount'

url += '&fromYear=' + fromYear

url += '&fromMonth=' + fromMonth

url += '&toYear=' + toYear

url += '&toMonth=' + toMonth

url += '&start=' + str(startValue)

url += '&count=0'

#download the page and save the result.

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

filename = cleanQuery + '/' + 'search-result' + str(startValue)

f = open(filename + ".html", 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

startValue = startValue + 10

#pause for 3 seconds

time.sleep(3)

def getIndivTrials(query):

import os, re, urllib.request, urllib.error, time, socket

failedAttempts = []

#import built-in python functions for building file paths

from os.path import join as pjoin

cleanQuery = re.sub(r'\W+', '', query)

searchResults = os.listdir(cleanQuery)

urls = []

#find search-results pages

for files in searchResults:

if files.find("search-result") != -1:

f = open(cleanQuery + "/" + files, 'r')

text = f.read().split(" ")

f.close()

#look for trial IDs

for words in text:

if words.find("browse.jsp?id=") != -1:

#isolate the id

urls.append(words[words.find("id=") +3: words.find("&")])

for items in urls:

#generate the URL

url = "http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/print.jsp?div=" + items

#download the page

socket.setdefaulttimeout(10)

try:

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

webContent = response.read()

#create the filename and place it in the new directory

filename = items + '.html'

filePath = pjoin(cleanQuery, filename)

#save the file

f = open(filePath, 'w')

f.write(webContent)

f.close

except urllib.error.URLError:

failedAttempts.append(url)

#pause for 3 seconds

time.sleep(3)

print("failed to download: " + str(failedAttempts))

Further Reading

For more advanced users, or to become a more advanced user, you may find it worthwhile to read about achieving this same process using Application Programming Interfaces (API). A website with an API will generally provide instructions on how to request certain documents. It’s a very similar process to what we just did by interpreting the URL Query Strings, but without the added detective work required to decipher what each variable does. If you are interested in the Old Bailey Online, they have recently released an API and the documentation can be quite helpful:

- Old Bailey Online API (http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/DocAPI.jsp)

- Python Best way to create directory if it doesn’t exist for file write? (http://stackoverflow.com/questions/273192/python-best-way-to-create-directory-if-it-doesnt-exist-for-file-write)