Close reading of primary sources is one of the most valuable skills historians can cultivate with their students. But as teachers, researchers, and students face unprecedented access to historical material in our “culture of abundance,” computer-assisted analysis of text is an increasingly viable and attractive skill. An insightful close reading of a single text, combined with a “distant reading” of a body of texts too large to comprehend on one’s own, can together offer students and researchers powerful new ways to understand historical documents.

Distant reading is one of the most well represented techniques in the Programming Historian’s cache of digital humanities tutorials. From identifying common phrases and sentence structures with AntConc to uncovering frequent keywords with MALLET, distant reading offers researchers an entryway into analyzing huge corpuses of text without requiring them to read through them line by line —— which could actually be an insurmountable task, depending on the scope of one’s archive, bibliography, or dataset.

Distant reading is a useful addition to any humanities researcher’s methodological toolkit. But it can also be really useful for teaching undergraduates how to research and analyze the many thousands of pages of archival documents that are being digitized every single day.

What might this look like in the classroom? Here’s an example from one of my own research and teaching areas, U.S. immigration history.

1892 to 1924 was a foundational era in the history of American immigration law and policy. 1892 was the first year when the regulation of immigration in the U.S. was brought under the supervision of a single federal office. In 1924, Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, a law that for the first time in American history limited immigration via numerical quotas based on national origin. Although the Johnson-Reed Act is known as one of the most exclusionary immigration laws of its time, it was hardly the first law in American history to restrict migration to the United States. The Page Act of 1875 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 paved the way for a tide of legislation that excluded many categories of immigrants from entering the country according to race, class, ability, sexuality, gender, and political affiliation.

There are many avenues for researching the evolution of exclusion in American immigration law. But one of the most accessible ways to do so is through the annual reports of immigration that the U.S. federal government published at the turn of the twentieth century. These annual reports are digitized and accessible to researchers and students through databases like HathiTrust, HeinOnline, and other databases available through many university library subscriptions.

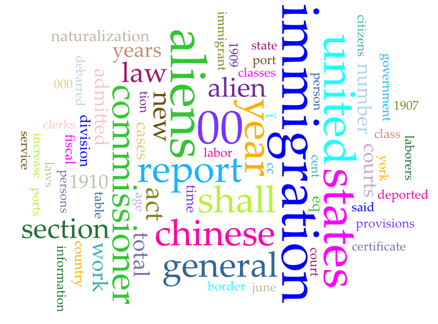

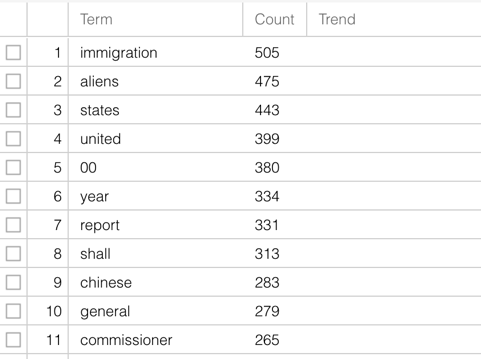

As a first foray into distant reading, instructors might encourage students to pick one annual report and run it through Voyant Tools. For example, a group of students could plug in the U.S. Department of Labor’s Annual Report on Immigration for the year 1910 and do a group think on the document’s major word frequencies.

Screenshots of a distant reading of the US Department of Labor’s Annual Report on Immigration, 1910, conducted with VoyantTools.org.

They might not be surprised, for example, that the words “immigration,” “united,” and “states” are some of the most recurring words in the document.

But what about the word “alien”? Students might discuss what the frequency of this word suggests about how government officials were thinking about immigrants at the time.

Or how about “Chinese”? Students might dig deeper into the report and read more closely about why Chinese immigration was such a concern to immigration officials at the time — and, at the same time, they might think about why “Chinese” is the only ethnic descriptor among the document’s most frequent words.

On the other end of the spectrum, students might discuss why words like “border” and “deportation” — words that are extremely important in today’s debates about immigration — are not among the most frequent words in the report.

The possibilities for coming up with questions about primary sources through distant reading become even more powerful when working with multiple texts. For example, an instructor who teaches themselves how to topic model with Programming Historian could pass that knowledge on to students by having them run every single annual report on immigration from 1892 to 1924 through the Topic Modeling Tool, a user-friendly interface for topic modeling that students who have no coding knowledge can use in the classroom. Using the Topic Modeling Tool with the annual reports from this era of immigration history would give students a chance to begin identifying the topics that were of concern to government officials, and begin to make observations about how those concerns changed over time.

As Ted Underwood notes, topic modeling may be especially useful for individuals who are approaching a set of texts without a particular research question in mind. Distant reading is a great way for students in particular to begin analyzing historical documents — and could also be a great way for students to start coming up with questions for research papers that will allow them to practice close readings of primary sources and further develop their digital research skills.

Have you taught with distant reading, or used a PH tutorial on distant reading in your classroom? Let us know! Tweet @ProgHist with the hashtag #teachDH and share your experiences with us.

About the author

Evan Taparata is a PhD candidate in history at the University of

Minnesota.