Here at the Programming Historian, we have a number of lessons focused on “distant reading.” These lessons pull from a variety of fields to demonstrate different ways to computationally surface patterns across a large collection of digital objects. But how do you build on those patterns as part of a research project? That question of what to do next is what the authors of this post have set out to answer.

In this blog post, authors Viola Wiegand, Michaela Mahlberg, and Peter Stockwell offer a sample of their research analyzing the language used in 19th century English novels. Using CLiC, a corpus analysis application that the authors are developing in a joint project between the University of Birmingham and the University of Nottingham, they explore the ‘fireplace pose’ in Dickens’s novels. Their goal is to “find textual patterns that are shared across novels and point to socially and culturally relevant behaviours and conventions in the real world.”

You can find out more about the CLiC Dickens research project on the project’s website.

If you are interested in learning how to use collocations and keywords in your own research, we recommend starting with Corpus Analysis with AntConc by Heather Froehlich. In this lesson, Froehlich introduces techniques from corpus linguistics, showing how to identify significant patterns of language use within and between sets of texts. And, as always, if you have an idea for a lesson or want to get involved with the Programming Historian, please visit our contribute page for more information.

CLiC (Corpus Linguistics in Context) is a web app specifically designed for the corpus linguistic study of literary texts. While CLiC shares much of its functionality with other corpus tools — similarly to what is described in the Programming Historian’s lesson ‘Corpus Analysis with AntConc’ — it also contains additional features that are particularly relevant to literary analysis. These include the ability to search subsets of the text – such as character speech – and a sorting function that goes beyond alphabetic sorting: the ‘KWICGrouper’, which this post focuses on. The CLiC web app has been developed as part of the CLiC Dickens project for the analysis of patterns in 19th century fiction, particularly novels by Charles Dickens. CLiC currently contains 15 Dickens novels and 29 novels by other 19th century authors and a corpus of 19th century children’s literature will soon be added.

Apart from aiding literary study, the corpus stylistic analysis of historical fiction can reveal insights into the social context of the texts more widely. In this post, we’ll discuss the so-called ‘fireplace pose’ in 19th century fiction that has been identified in literature and other cultural material from the time (for example paintings; see Korte 1997: 212). In CLiC it is possible, for example, to 1) trace textual patterns which describe how fictional characters sit or stand in front of the fire or look at it and 2) compare the patterns found in Dickens with those of other authors.

Let’s start with a simple concordance of fire in Dickens’s novels in CLiC. This gives us an overview of how the word is used: see Concordance 1. (Fireplace is, curiously, much less frequent and used in a different way!)

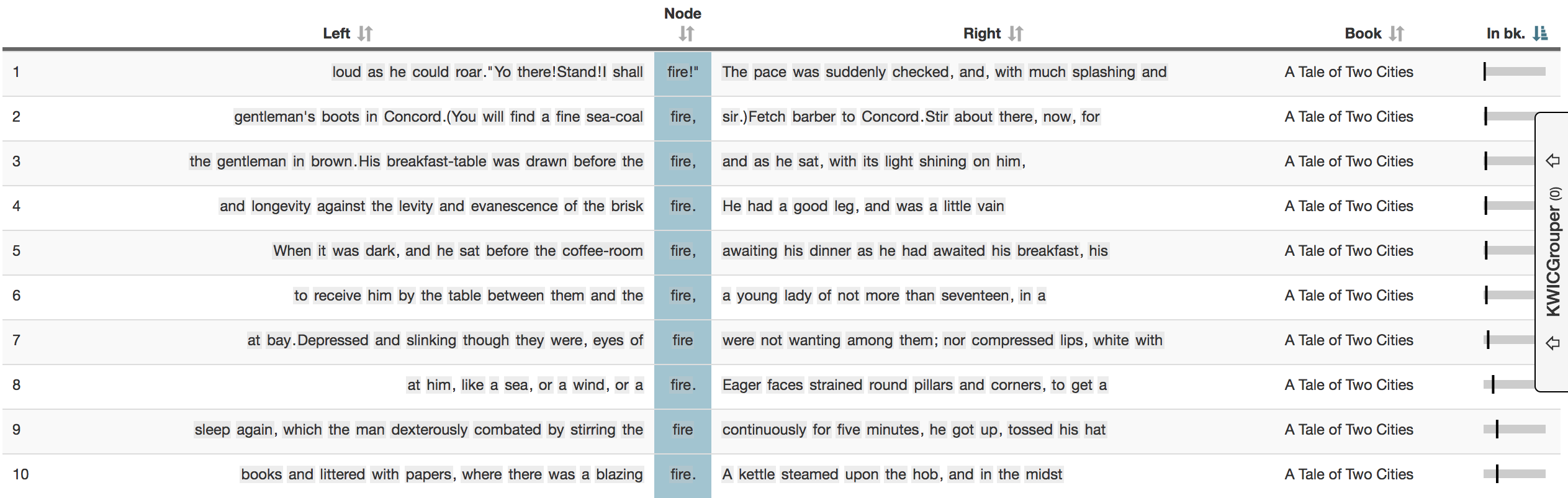

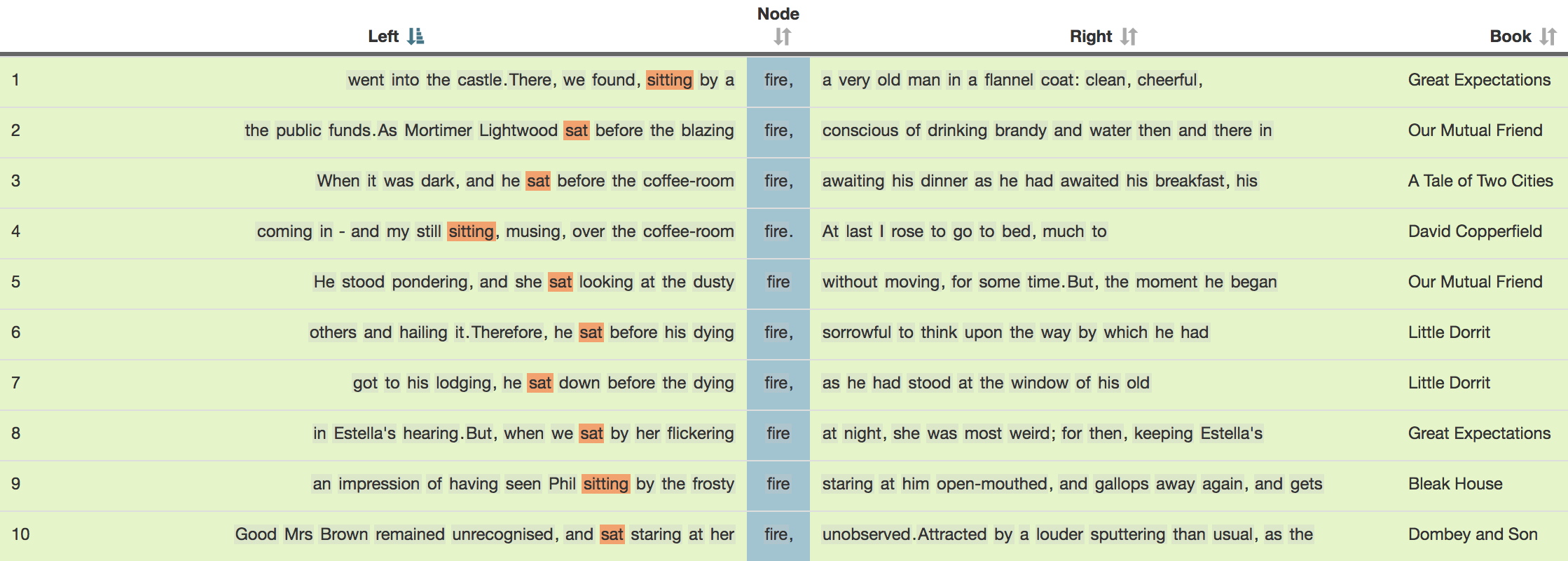

Concordance 1: The first ten concordance lines of fire (ordered by book)

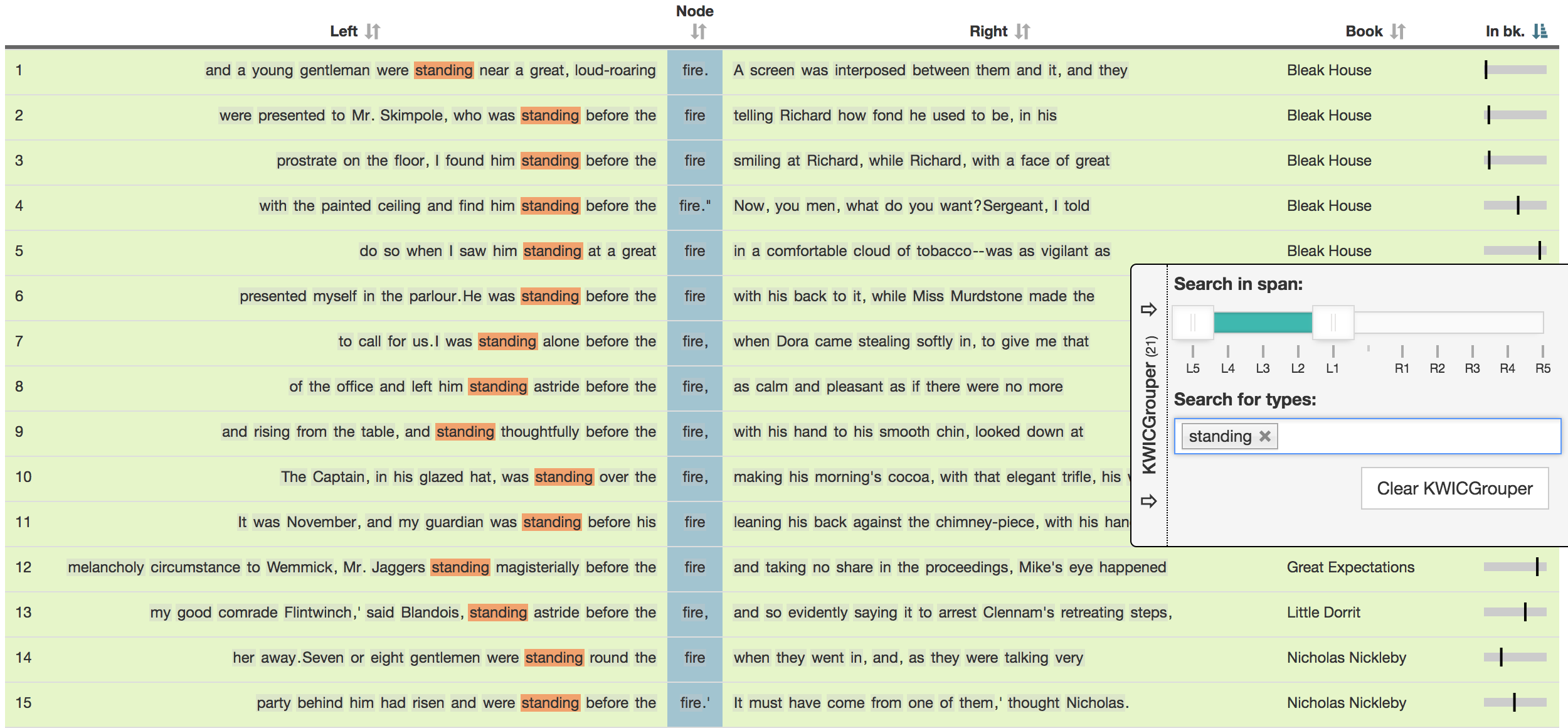

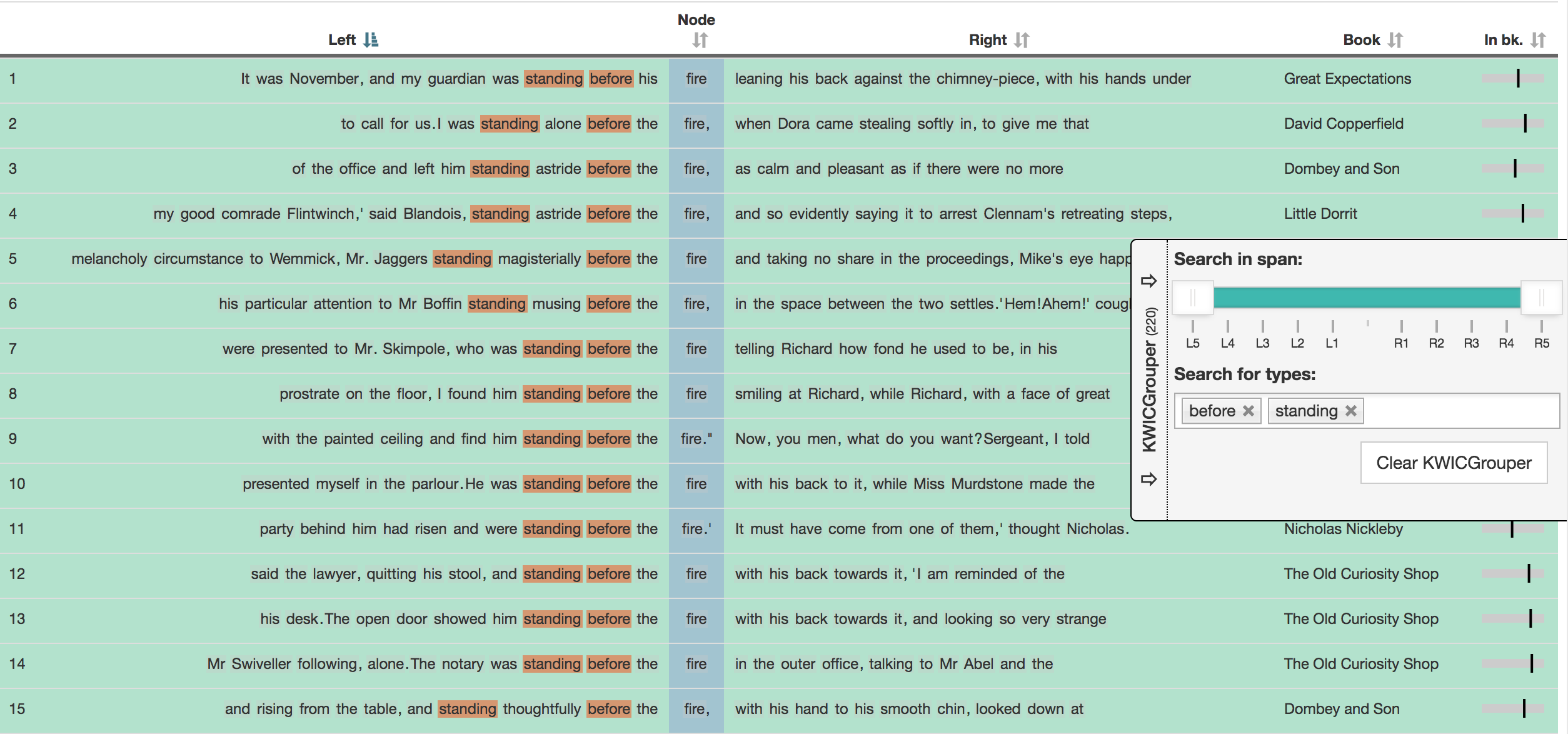

As the word is relatively frequent at approximately 1700 hits, it is easier to see patterns by sorting the concordance. Note for instance, that the first line in the concordance is an example of the verb fire. In order to group words with similar patterns and hence similar meanings together, the KWICGrouper allows us to interactively search for particular words in a specified span, highlighting the matching lines. The line colour changes with the number of matches. Those lines with the most matches are moved to the top. This semi-automatic grouping of concordance lines can help us identify qualitative groups of meaningful functions. (For a step-by-step explanation of the KWICGrouper watch a video tutorial on the CLiC Dickens blog.) In this case, the textual patterns to the left of fire are of particular interest for identifying character information. A search for standing on the left shows a pattern with before (Concordance 2). We can then add before to the search in order to group the lines together (Concordance 3).

Concordance 2: The first 15 concordance lines of fire co-occurring with standing on the left (ordered by book)

Concordance 3: All 15 concordance lines of fire co-occurring with both standing and before on the left

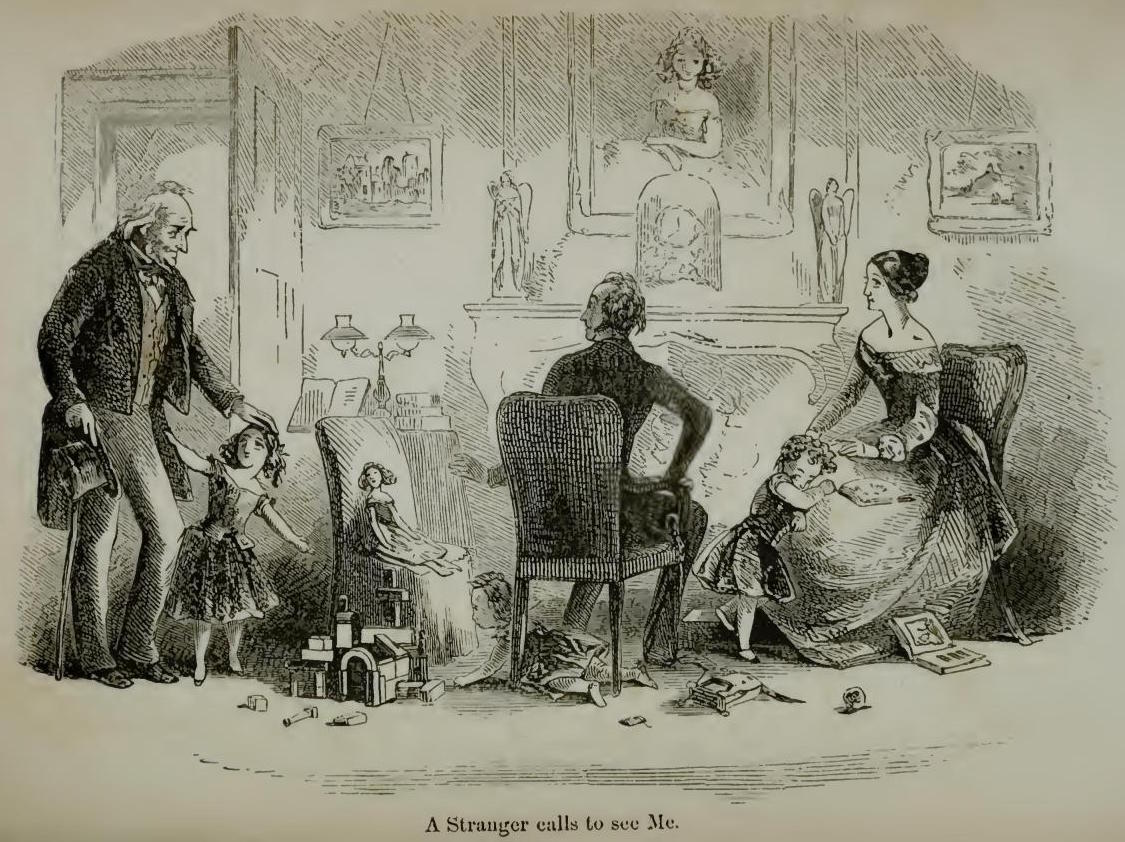

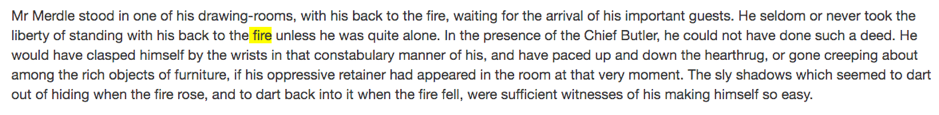

Looking at the characters represented by this pattern, it is striking that they are all male. While this may be due to the practical reason that women’s floor-length skirts could easily catch fire, it also suggests that it was mainly men who stood in such a prominent place in the house (see Korte 1997: 212 and Mahlberg 2013: 111-114), whereas women might be more likely to be sitting by the fire as in the image from David Copperfield.

Left image from David Copperfield, Chapter 63; right image from Dombey and Son, Chapter 51

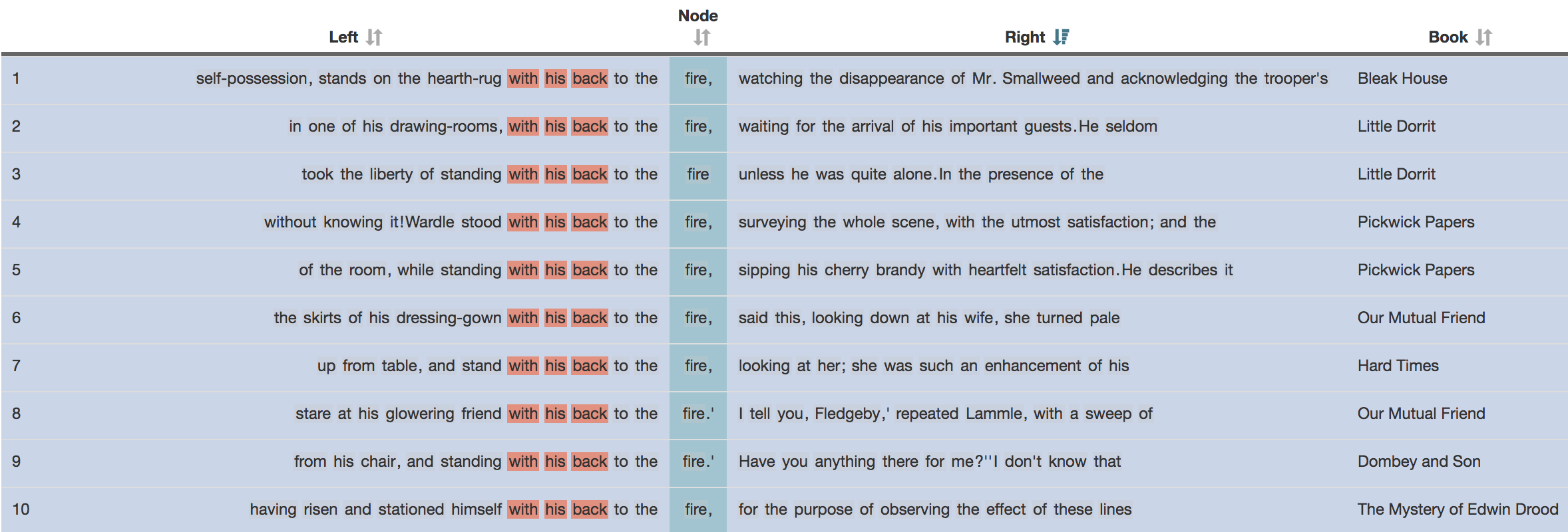

A frequent textual pattern indicating the fireplace pose is with his back to the fire (see Mahlberg 2013: 111). A character who stands with his back to the fire faces the room as illustrated in the picture from Dombey and Son and in line 4 of Concordance 4, which describes the character as surveying the whole scene. The female variant of the pattern, with her back to the fire, only occurs once in Dickens’s novels, describing a powerful female character (Mrs. Pipchin in Dombey and Son).

Concordance 4: Ten sample lines of with his back to the fire

The following example from Little Dorrit (Chapter 12) illustrates how the pose connotes power relations indicating that not all men were comfortable taking up this pose (see also Mahlberg 2013: 114):

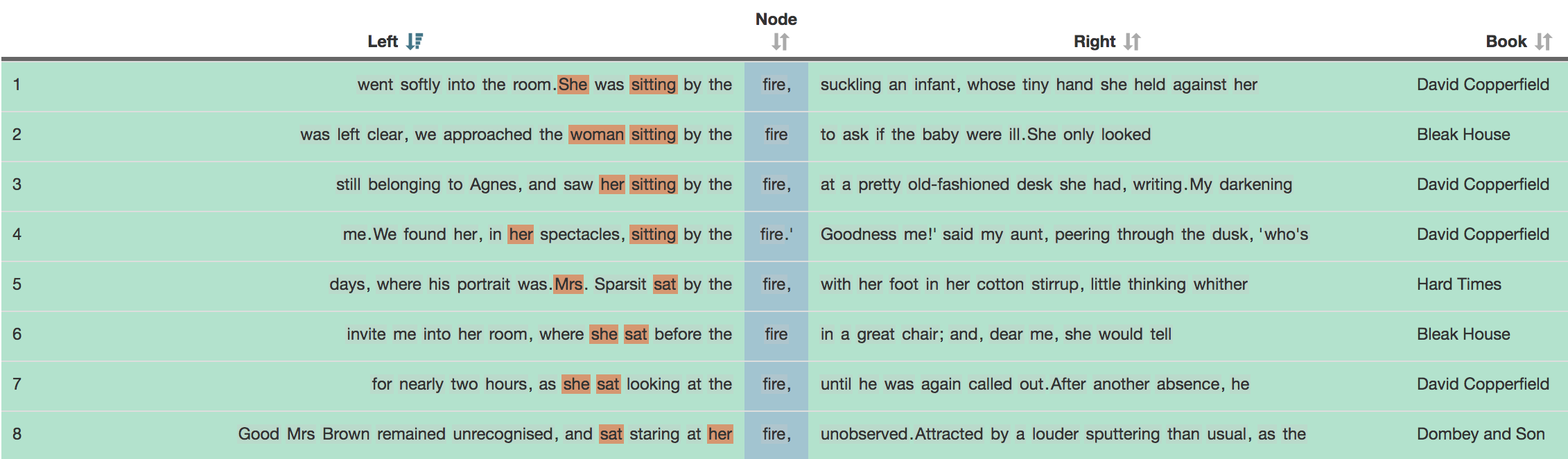

Female characters appear in other poses near the fire; for example, they can be found sitting near the fire, as shown in Concordance 5 (see also the image from David Copperfield above). As Concordance 6 illustrates, however, the pose of sitting near the fire is not restricted to any gender.

Concordance 5: Eight sample lines of female characters sitting by the fire

Concordance 6: Ten sample lines of characters sitting near the fire

A possible next step in the analysis in CLiC is to study the concordance lines in the novels by other 19th century authors. Apart from concordance analysis, other historical materials can complement the study of these textual patterns, such as images (both images in the books, as shown above, and other drawings/paintings of the time), as well as information from exhibitions and non-literary texts in general, for example etiquette books that can provide information on bodily movements and posture.

In this post, we have introduced corpus linguistic techniques for interrogating literature in order to find evidence of the body in Victorian England. We have seen that corpus methods can help find textual patterns that are shared across novels and point to socially and culturally relevant behaviours and conventions in the real world. In combination with other historical materials, CLiC can be used to approach questions on related social topics, such as class, the home and family life.

Further resources related to this post

· Blog post introducing the CLiC KWICGrouper (with video tutorial)

· Korte, B. (1997). Body Language in Literature. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

· Mahlberg, M. (2013). Corpus Stylistics and Dickens’s Fiction. New York & London: Routledge.

· Mahlberg, M., Stockwell, P., de Joode, J., Smith, C., O’Donnell, M. Brook, (2016) CLiC Dickens – Novel uses of concordances for the integration of corpus stylistics and cognitive poetics, Corpora, 11 (3), 433-463.

About the authors

Viola Wiegand is a Research Fellow on the AHRC-funded CLiC Dickens project at the University of Birmingham.

Michaela Mahlberg is the Chair in Corpus Linguistics and the Director of the Centre for Corpus Research at the University of Birmingham.

Peter Stockwell is the Associate Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Global Engagement (Europe) and Professor of Literary Linguistics at the University of Nottingham.